Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 15-3-2022

Date: 2024-02-22

Date: 2024-05-17

|

Two of the central questions which phonological theory has sought answers to are “why does rule X exist?” and “can rule Y exist?” Very many languages have a process changing velars into alveopalatals (k ! t ʃ ) before front vowels, and a rule voicing voiceless stops after nasals (mp ! mb) is also quite common. It is natural to wonder why such rules would occur in many languages, and a number of theoretical explanations have been offered to explain this. It is also important to also ask about imaginable rules: we want to know, for example, if any language has a rule turning a labial into an alveopalatal before a front vowel, one devoicing a voiced stop after a nasal, or one turning {s, m} into {l, k} before {w, ʃ}. Only by contrasting attested with imaginable but unattested phenomena do theories become of scientific interest.

Impossible rules. There is a clear and justified belief among phonologists that the rule {s, m} ! {l, k}/ _{w, ʃ} is “unnatural,” and any theory which predicts that such a rule is on a par with regressive voicing assimilation would not be a useful theory. We have seen that it is actually impossible to formulate such a process given the theory of distinctive features, since the classes of segments defining target and trigger, and the nature of the structural change, cannot be expressed in the theory. The fact that neither this rule nor any of the innumerable other conceivable random pairings of segments into rules has ever been attested in any language gives us a basis for believing that phonological rules should at least be “possible,” in the very simple technical sense expressed by feature theory. Whether a rule is possible or impossible must be determined in the context of a specific theory.

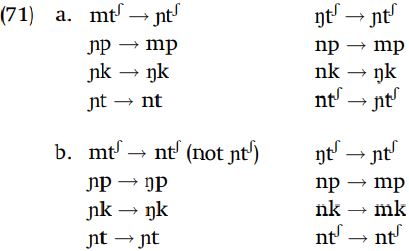

Another pair of rules which we might wonder about are those in (71).

The pattern of alternation in (a) is quite common, and was exemplified earlier as nasal place assimilation. The second pattern of alternation in (b), on the other hand, is not attested in any language. Given the nonexistence of the pattern (b), we may ask “why is this pattern not attested?”

The easy answer to this question is that pattern (b) is not phonetically natural. This begs the question of how we know what is a phonetically natural versus an unnatural pattern, and unfortunately the connection between “actually attested phonological rule” and “phonetically natural” is so close that some people may assume that commonly occurring rules are by definition phonetically natural, and unattested rules are unnatural. This is circular: if we are to preclude a pattern such as (b) as phonetically unnatural, there must be an independent metric of phonetic naturalness. Otherwise, we would simply be saying “such-and-such rule is unattested because it is unattested,” which is a pointless tautology.

Another answer to the question of why pattern (b) is not attested, but pattern (a) is, would appeal to a formal property of phonological theory. We will temporarily forgo a detailed analysis of how these processes can be formulated, but in one theory, the so-called linear theory practiced in the 1960s and 1970s, there was also no formal explanation for this difference and the rules in (b) were possible, using feature variable notation. By contrast, the nonlinear theory, intro-duced in the late 1970s, has a different answer: formalizing such rules is technically impossible, just as writing a rule {s, m} ! {l, k}/ _{w, ʃ} is impossible in classical feature theory. The mechanism for processes where the output has a variable value (i.e. the result can be either [+anterior] or [–anterior]) requires the target segment to take the same values for the features, and to take on all values within certain feature sets. The alternation in (b) does not have this property (for example, the change of /ɲp/ to [ŋp] does not copy the feature [labial]), and therefore according to the nonlinear theory this is an unformalizable rule. The process is (correctly) predicted to be unattested in human language.

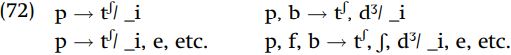

Unlikely rules. Now consider a rule p ! t ʃ / _{i, e}, which seems hardly different from k ! t ʃ / _{i, e}, except the latter is common, and the former is apparently not found in any language. Since we don’t know of examples, we must wonder why there is such a gap in what is attested. Perhaps if we had the “right theory,” every rule that is possible under a theory would actually be attested in some language. In both the linear and nonlinear theories, these are both technically possible rules.

One legitimate strategy is to assume that this is an accidental gap, and hope that further research will eventually turn up such a rule. Given that only a tiny fraction of the world’s languages have been surveyed, this is reasonable. There is a bit of danger in assuming that the apparent nonexistence of labial coronalization is an accidental gap, because we don’t want to mistakenly ignore the nonexistence of the imaginary rule /s, m/ ! [l, k]/_[w, ʃ ] as another accidental gap.

The difference between these two kinds of rules lies in an implicit estimation of how big the gap is between prediction and observation. A number of rules would fall under the rubric “labial coronalization,” which would be formalizable under standard feature theories:

If the rules /p/ ! [tʃ ] / _[i], /p/ ! [tʃ ] / _[i, e] and /p, f, b/ ! [t ʃ , ʃ, dʒ ] / _[i, e] were all attested and only the rule /p, b/ ! [t ʃ , dʒ ] / _[i] were missing, there would be no question that this is an accidental gap. The number of rules which can be formulated in standard theories is large, running in the millions or billions. If we can’t find one or some dozen particular rules in the hundred or so languages that we have looked at, this shouldn’t cause serious concern because the chance of finding any one rule out of the set of theoretically possible rules is fairly low, and this one gap is of no more significance than a failure to toss a million-sided coin a few hundred times and not have the coin land with side number 957,219 on top.

We should be a bit more concerned when we identify a somewhat large class – hundreds or perhaps even a thousand – of possible rules which are all unattested and which seem to follow a discernable pattern (i.e. “alveopalatalization of labials”). Remember though that we are dealing with a million-sided coin and only a few hundred tosses of the coin. The unattested set of rules represents perhaps a tenth of a percent of the logically possible set, and given the small size of the sample of phonological rules actually available to us, the chances of actually finding such a rule are still not very high.

The situation with the rule /s, m/ ! [l, k] / _[w, ʃ] is quite different. This rule is a representative of an immense class of imaginable rules formed by arbitrarily combining sounds in lists. If rules are unstructured collections of segments changing randomly in arbitrary contexts, then given a mere 8,192 (¼213) imaginable language sounds, there are around 1045,000 different ways to arrange those segments into rules of the type {..} ! {...} /_{...}, in comparison to around a billion ways with standard rule theory. Almost every rule which is theoretically predicted under the “random segment” theory falls into the class of rules of the type /s, m/ ! [l, k] / _[w, ʃ], and yet not a single one of these rules has been attested. Probability theory says that virtually every attested rule should be of this type, given how many of the imaginable arbitrary rules there are. This is why the lack of rules of the type /s, m/ ! [l, k] / _[w, ʃ] is significant – it represents the tip of a mammoth iceberg of failed predictions of the “random phoneme” theory of rules.

Another way to cope with this gap is to seek an explanation outside phonological theory itself. An analog would be the explanation for why Arctic mammals have small furry ears and desert mammals have larger naked ears, proportionate to the size of the animal. There is no independent “law of biology” that states that ear size should be directly correlated with average temperature, but this observation makes sense given a little knowledge of the physics of heat radiation and the basic structure of ears. In a nutshell, you lose a lot of body heat from big ears, which is a good thing in the desert and a bad thing in the Arctic. Perhaps there is an explanation outside the domain of phonological theory itself for the lack of labial coronalization in the set of attested rules.

What might be the functional explanation for the lack of such a process? We first need to understand what might be a theory-external, functional explanation for the common change k ! t ʃ / _{i, e}. In a vast number of languages, there is some degree of fronting of velar consonants to [kj ] before front vowels. The reason for this is not hard to see: canonical velars have a further back tongue position, and front vowels have a further front tongue position. To produce [ki], with a truly back [k] and a truly front [i], the tongue body would have to move forward a considerable distance, essentially instantaneously. This is impossible, and some compromise is required. The compromise reached in most languages is that the tongue advances in anticipation of the vowel [i] during production of [k], resulting in a palatalized velar, i.e. the output [kj i], which is virtually the same as [ci], with a “true palatal” stop.

The actual amount of consonantal fronting before front vowels that is found in a language may vary from the barely perceivable to the reasonably evident (as in English) to the blatantly obvious (as in Russian). This relatively small physiological change of tongue fronting has a disproportionately more profound effect on the actual acoustic output. Essentially a plain [k] sounds more like a [p] than like [c] ([k] has a lower formant frequency for the consonant release burst), and [tʃ ] sounds more like [t] or [tʃ ] (in having a higher burst frequency) than like [k], which it is physiologically more similar to. The acoustic similarity of alveopalatals like [tʃ ] and palatals like [tʃ ] is great enough that it is easy to confuse one for the other. Thus a child learning a language might (mis)interpret a phonetic alternation [k] ~ [tʃ ] as the alternation [k] ~ [tʃ ].

Explaining why k ! t ʃ / _{i, e} does exist is a first step in understanding the lack of labial coronalization before front vowels. The next question is whether there are analogous circumstances under which our unattested rule might also come into existence. Since the production of [p] and the production of [i] involve totally different articulators, a bit of tongue advancement for the production of [i] will have a relatively negligible effect on the acoustics of the release burst for the labial, and especially will not produce a sound that is likely to be confused with [tʃ ]. The constriction in the palatal region will be more open for /i/ after the release of /p/, because the tongue does not already produce a complete obstruction in that region (a maximally small constriction) as it does with /k/. It is possible to radically advance the tongue towards the [i]-position and make enough of a palatal constriction during the production of a [p] so that a more [tʃ ]-like release will result, but this will not happen simply as a response to a small physically motivated change, as it does with /k/. Thus the probability of such a change – p ! t ʃ – coming about by phonetic mechanisms is very small, and to the extent that phonological rules get their initial impetus from the grammaticalization of phonetic variants, the chances of ever encountering labial coronalization are slim.

Another approach which might be explored focuses on articulatory consequences of velar coronalization versus labial coronalization. Velars and alveolars involve the tongue as their major articulator, as does [tʃ ], whereas labials do not involve the tongue at all. We might then conjecture that there is some physiological constraint that prevents switching major articulators, even in phonological rules. But we can’t just say that labials never become linguals: they typically do in nasal assimilation. In fact, there is a process in the Nguni subgroup of Bantu languages (Zulu, Xhosa, Swati, Ndebele), where at least historically labials become alveopalatals before w, which is very close to the unattested process which we have been looking for. By this process, a labial consonant becomes a palatal before the passive suffix -w-, as in the following data from Swati.

This is a clear counterexample to any claim that labials cannot switch major articulator, and is a rather odd rule from a phonetic perspective (as pointed out by Ohala 1978). Rather than just leave it at that, we should ask how such an odd rule could have come into existence. In a number of Bantu languages, especially those spoken in southern Africa, there is a low-level phonetic process of velarization and unrounding where sequences of labial consonant plus [w] are pronounced with decreased lip rounding and increased velar constriction, so that underlying /pw/ is pronounced as [pɯ], with [ɯ] notating a semi-rounded partial velar constriction. The degree of velar constriction varies from dialect to dialect and language to language, and the degree of phonetic constriction increases as one progresses further south among the Bantu languages of the area, so in Karanga Shona, /pw/ is pronounced with a noticeable obstruent-like velar fricative release and no rounding, as [px ]. The place of articulation of the velar release shifts further forward depending on the language and dialect, being realized as [pç ] in Pedi, or as [pʃ ] in Sotho, and finally as [tʃ ] in Nguni. So what seems like a quite radical change, given just the underlying-to-surface relation /p/ ! [t ʃ ] in Nguni, is actually just the accumulated result of a number of fortuitously combined, less radical steps.

One of the current debates in phonology – a long-standing debate given new vitality by the increased interest in phonetics – is the question of the extent to which phonological theory should explicitly include reference to concepts rooted in phonetics, such as ease of articulation, perceptibility, and confusability, and issues pertaining to communicative function. Virtually every imaginable position on this question has been espoused, and it is certain that the formalist/functionalist debate will persist unresolved for decades.

|

|

|

|

"عادة ليلية" قد تكون المفتاح للوقاية من الخرف

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ممتص الصدمات: طريقة عمله وأهميته وأبرز علامات تلفه

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

المجمع العلمي يعلن إطلاق المسابقة الجامعية الوطنية لأفضل بحث تخرّج حول القرآن الكريم

|

|

|