Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-04-19

Date: 23-3-2022

Date: 2023-06-19

|

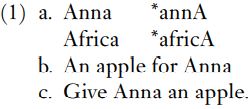

Since we are more used to thinking explicitly about written language than about our speech, one way of approaching this issue of abstraction is through our conscious knowledge of the rules of writing. When children learn to write, they have to master the conventions governing the use of capital and lower-case letters. Children often tend to learn to write their name before anything else, and this will have an initial capital; and children are also great generalizers, and indeed over-generalizers; for instance, first words often have a much wider range of meanings than their adult equivalents. Thus, for a one-year-old, cat may mean ‘any animal’ (whether real, toy, or picture), tractor ‘any vehicle’, and Daddy ‘any male adult’; these broad senses are later progressively narrowed down. It follows that children may at first try to write all words with initial capitals, until they are taught the accepted usage, which in modern English is for capitals to appear on proper names, I, and the first word in each sentence, and lower-case letters elsewhere, giving the prescribed patterns in (1).

Precisely how the capital and lower-case letters are written by an individual is not relevant, as long as they are recognizable and consistently distinct from other letters – an needs to be distinguished from on, and An from In, but it does not especially matter whether we find a  or a for lower-case, and A

or a for lower-case, and A  or A for capital; it all depends who we copy when we first learn, what our writing instruments and our grip on them are like, or typographically, which of the burgeoning range of fonts we fancy

or A for capital; it all depends who we copy when we first learn, what our writing instruments and our grip on them are like, or typographically, which of the burgeoning range of fonts we fancy

Again, we seem readily able to perceive that all these subtly different variants can be grouped into classes. There is a set of lower-case and a set of capital letters, and the rules governing their distribution relate to those classes as units, regardless of the particular form produced on a certain occasion of writing. Moreover, the lower-case and capital sets together belong to a single, higher-order unit: they are all forms, or realizations of ‘the letter a’, an ideal and abstract unit to which we mentally compare and assign actual written forms. ‘The letter a’ never itself appears on paper, but it is conceptually real for us as users of the alphabet: this abstract unit is a grapheme, symbolized>a< ; triangle brackets are conventionally used for spellings.

The choice of symbol is purely conventional: since it is a conceptual unit, and since we do not know what units look like in the brain, we might as well use an arbitrary sign like or give it a name

or give it a name is Annie Apple in the children’s Letterland series for beginning readers. However, it is convenient to use a form that looks like one of the actual realizations, as this will help us to match up the abstract grapheme with the actual graphs which manifest it in actual writing.

is Annie Apple in the children’s Letterland series for beginning readers. However, it is convenient to use a form that looks like one of the actual realizations, as this will help us to match up the abstract grapheme with the actual graphs which manifest it in actual writing.

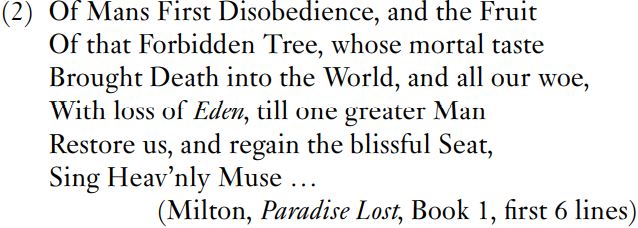

The rules governing the distribution of and other graphemes are not, however, absolute natural laws. Learning that proper names and sentences begin with capitals is appropriate for a child writing modern English, but not for a child learning German, who would need to learn instead that all nouns (not just Anna and Afrika but also Apfel ‘apple’) always begin with a capital letter, as well as all sentences. A similar strong tendency is observable in earlier stages of English too, and although literary style is not absolutely consistent in this respect, there are many more capitals in the work of a poet like John Milton, for instance, than in written English today; see (2).

and other graphemes are not, however, absolute natural laws. Learning that proper names and sentences begin with capitals is appropriate for a child writing modern English, but not for a child learning German, who would need to learn instead that all nouns (not just Anna and Afrika but also Apfel ‘apple’) always begin with a capital letter, as well as all sentences. A similar strong tendency is observable in earlier stages of English too, and although literary style is not absolutely consistent in this respect, there are many more capitals in the work of a poet like John Milton, for instance, than in written English today; see (2).

|

|

|

|

تفوقت في الاختبار على الجميع.. فاكهة "خارقة" في عالم التغذية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أمين عام أوبك: النفط الخام والغاز الطبيعي "هبة من الله"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

قسم شؤون المعارف ينظم دورة عن آليات عمل الفهارس الفنية للموسوعات والكتب لملاكاته

|

|

|