Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Synonyms

المؤلف:

Patrick Griffiths

المصدر:

An Introduction to English Semantics And Pragmatics

الجزء والصفحة:

26-2

10-2-2022

1431

Synonyms

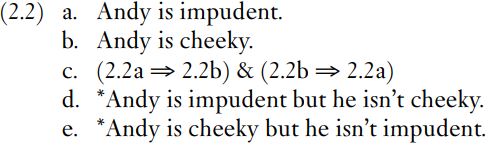

Synonymy is equivalence of sense. The nouns mother, mom and mum are synonyms (of each other). When a single word in a sentence is replaced by a synonym – a word equivalent in sense – then the literal meaning of the sentence is not changed: My mother’s/mum’s/mom’s family name was Christie. Sociolinguistic differences (such as the fact that mom and mum are informal, and that mom would typically be used by speakers of North American English while mum has currency in British English) are not relevant, because they do not affect literal meaning. (As explained in earlier, literal meaning is abstracted away from contexts of use.) Sentences with the same meaning are called paraphrases. Sentences (2.2a, b) are paraphrases. They differ only by intersubstitution of the synonyms impudent and cheeky.

(Remember that ⇒ represents entailment, and an asterisk at the beginning of a sentence signals that it has serious meaning problems.)

Sentence (2.2a), if it is true, entails – guarantees the truth of – sentence (2.2b), provided it is the same Andy at the same point in time. When (2.2a) is true, (2.2b) must also be true. To establish paraphrase we have to do more, however, than show that one sentence entails another: the entailment has to go both ways, (2.2a) entails (2.2b) and it is also the case that (2.2b) entails (2.2a), as summarized in (2.2c). In normal discourse, both (2.2d) and (2.2e) are contradictions, because entailments cannot be cancelled. When an entailed sentence is false, sentences that entail it cannot be true.

What has been said about the synonyms impudent and cheeky can be employed in two different directions. One way round, if you are doing a semantic description of English and you are able to find paraphrases such as (2.2a, b) differing only in that one has cheeky where the other has impudent, then you have evidence that these two adjectives are synonyms of each other. Alternatively, if someone else’s description of the semantics of English lists impudent and cheeky as synonyms, that would tell you that they are predicting that sentences such as (2.2a, b) are paraphrases of one another, which is to say that the two-way entailments listed in (2.2c) hold. The claim that impudent is a synonym of cheeky predicts that sentences such as (2.2d, e) are contradictions; or the contradictions can be cited as evidence that the two words are synonymous.

Paraphrase between two sentences depends on entailment, since it is defined as a two-way entailment between the sentences. The main points of the previous paragraph are that entailments indicate sense relations between words, and sense relations indicate the entailment potentials of words.

How can one find paraphrases? Well, you have to observe language in use, think hard and invent test sentences for yourself, to try to judge whether or not particular entailments are present. The examples in (2.3) show how the conjunction so can be used in test sentences for entailment.

So generally signals that an inference is being made. When we are dealing with sentences out of context, as in cases when it does not matter who the Andy in (2.3a, b) is, then the inferences are entailments rather than some kind of guess based on knowledge of a situation, or of the character of a particular Andy.

Sentence (2.3a) is an entirely reasonable argument. People who accept it as reasonable accept (tacitly at least) that Andy is cheeky entails that ‘Andy is impudent’. Sentence (2.3b) is also an entirely reasonable argument. People who accept it as reasonable are accepting that Andy is impudent entails ‘Andy is cheeky’. If both of the arguments (2.3a, b) are accepted as reasonable, then we have two-way entailment – paraphrase – between Andy is cheeky and Andy is impudent and we can conclude that the two adjectives are synonymous with each other. (People who do not accept (2.3a, b) as reasonable arguments perhaps do not know either or both of the adjectives in question, or use meanings for one or both of these words that are different to those used by the author, or they are focusing on a difference that is the concern of other branches of linguistics: sociolinguistics and stylistics.)

Some other pairs of synonymous adjectives are listed in (2.4).

It is important to realize that the two-way, forward-and-back entailment pattern illustrated in (2.2c) is defining for synonymy. Huge and big are related in meaning, but they are not synonyms, as confirmed by the fact that, while The bridge is huge entails The bridge is big, we do not get entailment going the other way; when The bridge is big is true, it does not have to be true that The bridge is huge (it might be huge, but it could be big without being huge).

Synonymy is possible in other word classes, besides adjectives, as illustrated in (2.5).

In principle, synonymy is not restricted to pairs of words. The triplet sofa, settee and couch are synonymous.

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)