Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Constituent structure

المؤلف:

Jim Miller

المصدر:

An Introduction to English Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

11-1

28-1-2022

1640

Constituent structure

Heads, modifiers and arrangements of words

We discussed the relations between heads and modifiers and at the end , labelled these relations ‘dependencies’. Dependencies are central to syntax. To make sense of a clause or sentence in written language or of a series of clauses in spontaneous speech, we have to pick out each head and the words that modify it. This task is made easier by the organization of words into phrases and clauses. Speakers and writers produce words and phrases one after the other. (It does not matter whether the writer sets out words from left to right, as in English texts, or right to left, as in Arabic texts.) Heads and modifiers tend to occur next to each other. For instance, in English, nouns can be modified by various types of words and phrases – adjectives, prepositional phrases and relative clauses, not to mention words such as a, the, this and some. Examples are given in (1)

In (1a), house is modified by the definite article the; in (1b) it is modified by the definite article and by the adjective splendid. The definite article, the indefinite article a and demonstratives such as this and that precede their head noun, but certain modifiers follow their head noun. Examples are the prepositional phrase on the hilltop in (1c) and the relative clause which they built out of reinforced concrete in (1d).

In noun phrases in some other languages, the order of head and modifiers follows a stricter pattern, with all modifiers either preceding or following the head. In French, for example, most adjectives and all prepositional phrases and relative clauses follow the noun, although the definite and indefinite articles precede it. This is demonstrated in (2).

The adjective splendid, the prepositional phrase sur la colline and the relative clause qu’ils ont construite en béton armé all follow the head noun. At this point, we come up against one of the interesting (or annoying) facts of French and indeed of all human languages: most patterns have exceptions. In French, a small number of adjectives precede their head noun, as in une jolie ville (a pretty town) and un jeune étudiant (a young student), but the large majority of adjectives follow their head noun.

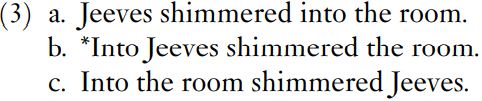

Returning to English, we see that in certain declarative clauses the modifiers of prepositions follow their head preposition. Example (3a) shows the typical pattern, with the preposition into followed by the kitchen; (3b) shows an impossible example, with into at the beginning of the clause and the kitchen at the end; and (3c) shows the correct structure.

In some other English clauses, the noun-phrase modifier of a preposition can be separated from its head preposition. Example (4a) is the typical way of questioning room in (3a). In it, which room is at the front of the clause, and into is ‘stranded’ at the end of the clause. Example (4b) is also acceptable but is mainly used in formal writing.

We can note in passing that similar stranding is found in clauses introduced by which or who. In formal writing, a preposition plus which/who turns up at the front of the clause, as in the room into which Jeeves shimmered. In informal writing and in informal speech, the preposition is left behind at the end of the clause, as in the room which Jeeves shimmered into.

Verbs can be modified by a number of items, as we have seen in Example (5) shows the order of modifiers in a neutral clause, that is, a clause in which no particular word or phrase is emphasized.

Barbara, the subject noun phrase, precedes the verb, but the other modifiers follow it – the noun phrase (direct object) the results, the prepositional phrase (oblique object) to Alan and the prepositional phrase (adverb of time) on Tuesday. Typically, the subject and the direct object are immediately next to the verb, the subject preceding it, the direct object following it. In (5), the subject Barbara and the direct object the results are next to the verb. In other languages, the verbs and modifiers are arranged in patterns that put all the modifiers either before or after the verb. In written Turkish, for instance, the order in neutral clauses is that the verb comes last, preceded by all the modifiers.

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)