تاريخ الفيزياء

علماء الفيزياء

الفيزياء الكلاسيكية

الميكانيك

الديناميكا الحرارية

الكهربائية والمغناطيسية

الكهربائية

المغناطيسية

الكهرومغناطيسية

علم البصريات

تاريخ علم البصريات

الضوء

مواضيع عامة في علم البصريات

الصوت

الفيزياء الحديثة

النظرية النسبية

النظرية النسبية الخاصة

النظرية النسبية العامة

مواضيع عامة في النظرية النسبية

ميكانيكا الكم

الفيزياء الذرية

الفيزياء الجزيئية

الفيزياء النووية

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء النووية

النشاط الاشعاعي

فيزياء الحالة الصلبة

الموصلات

أشباه الموصلات

العوازل

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء الصلبة

فيزياء الجوامد

الليزر

أنواع الليزر

بعض تطبيقات الليزر

مواضيع عامة في الليزر

علم الفلك

تاريخ وعلماء علم الفلك

الثقوب السوداء

المجموعة الشمسية

الشمس

كوكب عطارد

كوكب الزهرة

كوكب الأرض

كوكب المريخ

كوكب المشتري

كوكب زحل

كوكب أورانوس

كوكب نبتون

كوكب بلوتو

القمر

كواكب ومواضيع اخرى

مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

النجوم

البلازما

الألكترونيات

خواص المادة

الطاقة البديلة

الطاقة الشمسية

مواضيع عامة في الطاقة البديلة

المد والجزر

فيزياء الجسيمات

الفيزياء والعلوم الأخرى

الفيزياء الكيميائية

الفيزياء الرياضية

الفيزياء الحيوية

الفيزياء العامة

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء

تجارب فيزيائية

مصطلحات وتعاريف فيزيائية

وحدات القياس الفيزيائية

طرائف الفيزياء

مواضيع اخرى

Geocentric motion of a planet

المؤلف:

A. Roy, D. Clarke

المصدر:

Astronomy - Principles and Practice 4th ed

الجزء والصفحة:

p 158

7-8-2020

1809

Geocentric motion of a planet

Once the sidereal period T of a planet is found, also the mean heliocentric distance a, the velocity V

of the planet in its orbit (assumed circular) can be calculated. Thus,

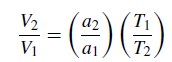

For two planets, therefore, the ratio of their orbital velocities is given by

(1)

(1)

where the subscripts 1 and 2 refer to the inner and outer planet respectively. Putting in values, it is found that the velocity of the inner planet is greater than that of the outer. As we shall see later, Kepler found that for any planet,

a3 ∝ T 2

or

a3 = kT2 (2)

where k is a constant.

Then by equation (2),

According to Kepler, therefore, we may write for the two planets,

Substituting for T1 and T2 in equation (12.3), we obtain,

(3)

(3)

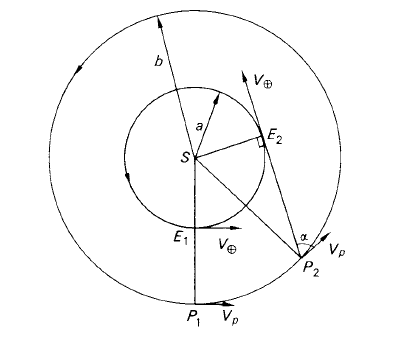

In figure 1, the orbits of the Earth and a planet are shown, the radii of the orbits (assumed

circular and coplanar) being a and b units respectively. Since the planet is a superior one, b is greater

than a.

At opposition, the positions of the planet and Earth are P1 and E1 and their velocity vectors are shown as VP and V⊕ respectively, tangential to their orbits.

Now by equation (3), VP < V⊕ and so the angular velocity of the planet as observed from the Earth is

and is in a direction opposite to the orbital movement. It is, therefore, retrograde at opposition.

Figure 1. The velocities of the Earth and a superior planet produce retrograde motion of the planet (P1) at opposition and direct motion of the planet (P2) at quadrature.

At the following quadrature, the positions of planet and Earth are P2 and E2, where ∠SE2P2 = 90◦. The Earth’s orbital velocity V⊕ is now along the line P2E2 but the planet’s velocity VP has a component VP sin α, perpendicular to E2P2. The other component VP cos α lies along the line P2E2 and, like the Earth’s velocity V⊕, does not contribute to the observed angular velocity of the planet. This geocentric angular velocity at quadrature is, therefore,

and is seen to be in the same direction as the orbital movement. It is thus direct at quadrature.

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)