Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Complement clauses

المؤلف:

PAUL R. KROEGER

المصدر:

Analyzing Grammar An Introduction

الجزء والصفحة:

P220-C12

2026-01-22

28

Complement clauses

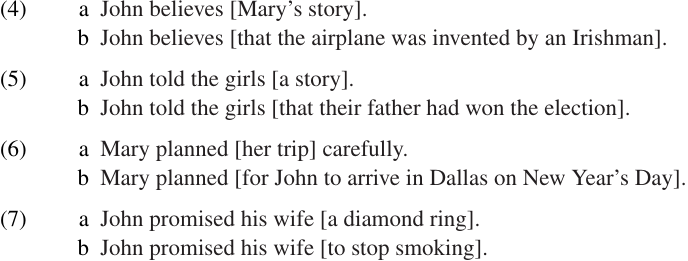

We have dealt primarily with simple clauses whose complements are expressed as NPs or (in the case of oblique arguments) PPs. However, many verbs also allow or require a clausal complement. Examples (4–7) show that, for some verbs, either an NP or a complement clause may occur in the same position. The complement clause may be either FINITE (i.e. tense-bearing), as in (4b) and (5b), or NONFINITE as in (6b) and (7b).

Notice that complement clauses are often introduced by a special word (or, in some languages, a particle) which is called a COMPLEMENTIZER. In English, the choice of verb form is related to the choice of complementizer. That is used to introduce a finite complement, as in (4b) and (5b). Infinitival complements take for if they have an overt (visible) subject, as in (6b); no complementizer is used when there is no overt subject, as in (7b).

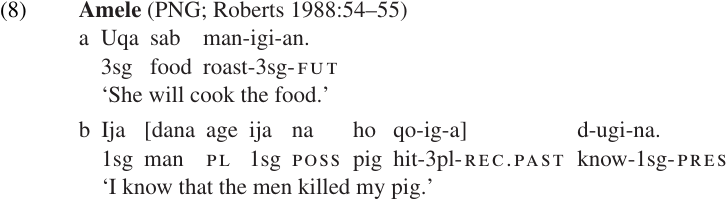

As noted above, complement clauses frequently occupy the same position as NP objects. In languages where direct objects precede the verb, complement clauses often precede the verb as well. For example, the basic word order in Amele is SOV, as illustrated in (8a). Complement clauses in Amele normally precede the verb, as in (8b).

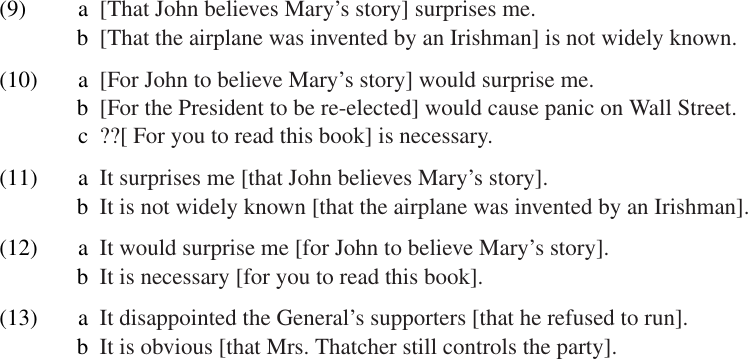

Some examples of complement clauses in subject position are given in (9–10). In normal spoken style it is usually more natural to rephrase such sentences using a dummy subject, as in (11–13); this construction is called EXTRAPOSITION.

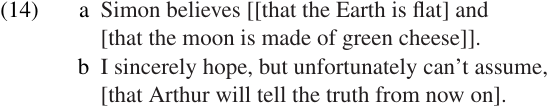

The fact that the complementizer and the clause which it introduces always stay together in the extraposition examples (11–13) suggests that these two elements form a constituent in the Phrase Structure. Further evidence for the existence of such a constituent is provided by examples like those in (14):

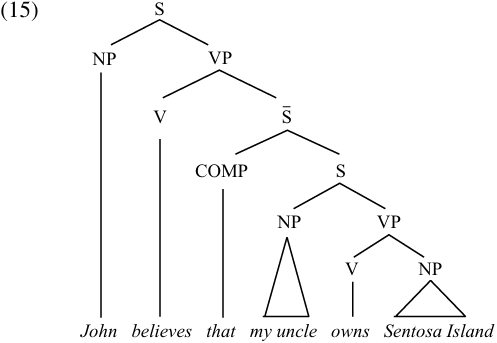

This constituent is normally labeled S՛ or S̄ (pronounced “S-bar”). It contains two daughters: COMP (for “complementizer”) and S (the complement clause itself). This structure is illustrated in the tree diagram in (15), which represents a sentence containing a finite clausal complement.

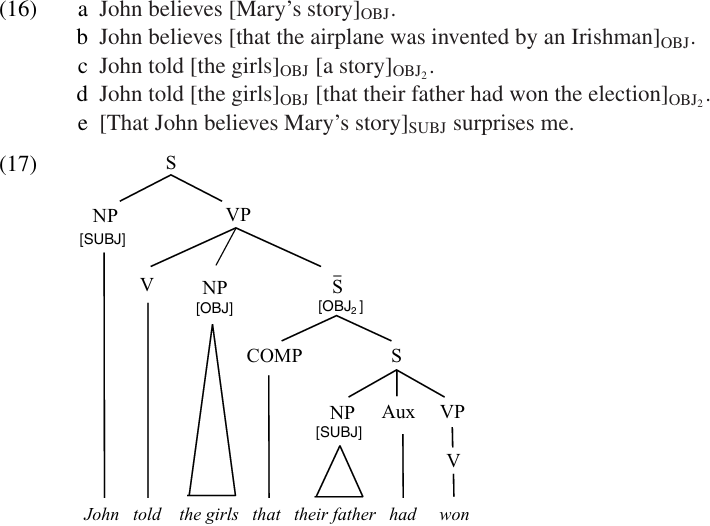

As we noted in (4–7), complement clauses can often occur in the same position as NP complements. This observation suggests that a complement clause may bear the same Grammatical Relation as the NP which it replaces, as indicated in (16). This is a somewhat controversial issue; some linguists have argued that complement clauses must bear a distinct Grammatical Relation.1 But, for the sake of simplicity, we will assume the analysis suggested in (16). An annotated tree diagram based on example (16d) is shown in (17).

Subordinate clauses in general, and complement clauses in particular, often have structural features which are not found in main clauses or independent sentences. Some of the structural features that need to be considered in analyzing and comparing different types of subordinate clause include:

a VERB FORM: Main clause statements and questions normally contain a finite verb. But the verb in some kinds of subordinate clause may be non-finite (e.g. an infinitive or participle), or appear in a different mood (e.g. subjunctive); or the subordinate verb may have to be nominalized.2

b SUBJECT: Certain types of subordinate clause lack a subject NP, either obligatorily or optionally. In other cases, the only permissible subject of the subordinate clause is a pronoun which is co-referential with some element of the matrix clause. Other types of subordinate clause may contain an independent subject NP, just like a main clause.

c WORD ORDER: A subordinate clause may be subject to different word order constraints from a main clause. There is often less freedom or variability in the word order of a subordinate clause than in a main clause.

d MATRIX VERB: Since complement clauses are selected (subcategorized for) by a specific matrix verb, it is important to identify which verbs select which type of clausal complement.

e COMPLEMENTIZER: Different types of complement clause may require different complementizers.

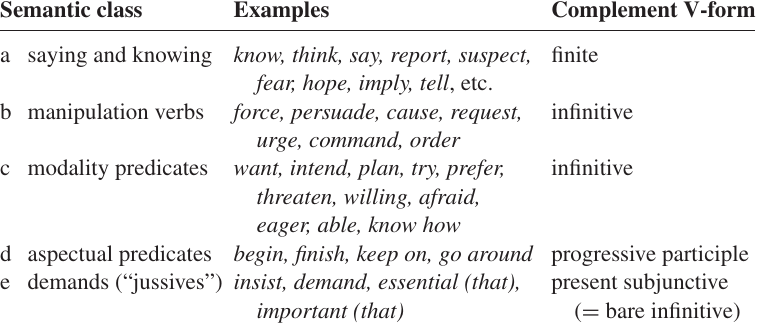

As mentioned in point (d), the form of a complement clause is often determined by the specific verb that occurs in the matrix clause. Verbs that belong to the same general semantic class often take the same type of complement. Some examples of various classes of English predicates follow. Example sentences for each class are given in (18) below.3

(18) a John believes [that the airplane was invented by an Irishman].

b John told the girls [that their father had won the election].

c John persuaded his wife [to sell her old car].

d John intends [to buy his brother’s rubber estate].

e Next week John will begin [studying for his A-levels].

f John keeps on [looking for a way to retire at age 35].

g I insist [(that) this man be arrested immediately].

h It is essential [that the President sign this document today].

In terms of the important structural features listed above, we might write brief descriptions of these constructions along the following lines:

(19) a English verbs of saying and knowing take a complement clause introduced by that. This complement clause has essentially the same structure as an independent sentence, including a finite verb, a full NP subject, normal word order, and the normal range of possible auxiliary verbs.

b English manipulation and modality predicates (verbs like persuade and intend) take a complement clause whose verb appears in the infinitive, preceded by to. These complement clauses have no complementizer and no subject. The subject of the complement clause is understood to be the same as the subject or object of the matrix clause.

Complement clauses which contain their own subject NP, like those in (18a, b, g, h) are sometimes referred to as SENTENTIAL COMPLEMENTS, because they contain all the essential parts of a sentence. In most languages, a complement clause will have its own subject whenever the complement verb is finite. Complement clauses which lack a subject NP, like those in (18c–f), can be analyzed as a special type of predicate complement.4

1. For example, there are a few English verbs that take two NP objects (OBJ and OBJ2) plus a clausal complement: Henry bet [his cousin] [ten dollars] [that Brazil would win the World Cup]. Since no English verb takes three NP objects, it is not clear what the GR of the complement clause would be in this example. Also, it has been argued that in some languages clausal complements which bear the OBJ relation have different grammatical properties from those which do not, even though they may occur in the same phrase-structural positions.

2. See Derivational morphology for a discussion of nominalization.

3. Only the primary usage of each matrix verb is noted here. Of course, many verbs have more than one sense. Thus, say can be used as a manipulation verb, as in John says to meet him in the library. Similarly, persuade can be used as a verb of speaking, as in Arthur persuaded me that he was innocent, etc.

4. See Kroeger (2004), Lexical entries and well-formed clauses for a detailed discussion of these constructions.

الاكثر قراءة في Sentences

الاكثر قراءة في Sentences

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)