High-temperature superconductors

المؤلف:

Peter Atkins, Tina Overton, Jonathan Rourke, Mark Weller, and Fraser Armstrong

المؤلف:

Peter Atkins, Tina Overton, Jonathan Rourke, Mark Weller, and Fraser Armstrong

المصدر:

Shriver and Atkins Inorganic Chemistry ,5th E

المصدر:

Shriver and Atkins Inorganic Chemistry ,5th E

الجزء والصفحة:

ص617-620

الجزء والصفحة:

ص617-620

2025-10-11

2025-10-11

261

261

High-temperature superconductors

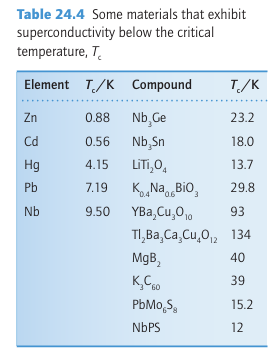

Key point: High-temperature cuprate superconductors have structures related to perovskite. The versatility of the perovskites extends to superconductivity because most of the high temperature superconductors (which were first reported in 1986) can be viewed as variants of the perovskite structure. Superconductors have two striking characteristics. Below a critical temperature, Tc (not to be confused with the Curie temperature of a ferroelectric, TC), they enter the superconducting state and have zero electrical resistance. In this super conducting state they also exhibit the Meissner effect, the exclusion of a magnetic field. The Meissner effect is the basis of the common demonstration of superconductivity in which a pellet of superconductor levitates above a magnet. It is also the basis for a number of potential applications of superconductors that include magnetic levitation, as in MAGLEV trains. Following the discovery in 1911 that mercury is a superconductor below 4.2 K, physicists and chemists made slow but steady progress in the discovery of superconductors with higher values of Tc at a rate of about 3 K per decade. After 75 years, Tc had been edged up to 23 K in Nb3Ge. Most of these superconducting materials were metal alloys, although superconductivity had been found in many oxides and sulfides (Table 24.4); magnesium diboride is superconducting below 39 K (see Box 13.4). Then, in 1986, the

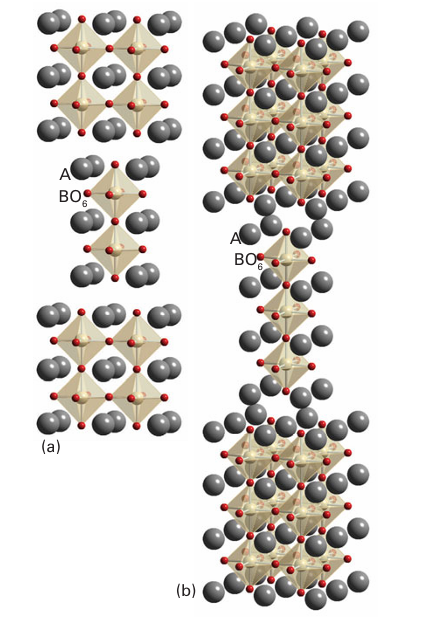

Figure 24.22 The Ruddlesden–Popper phases of stoichiometry (a) A3 B2O7 and (b) A4B3O10 formed respectively from two and three perovskite layers of linked BO6 octahedra separated by A-type cations.

first high-temperature superconductor (HTSC) was discovered. Several materials are now known with Tc well above 77K, the boiling point of the relatively inexpensive refrigerant liquid nitrogen, and in a few years the maximum Tc was increased by more than a factor of five to around 134 K.

Two types of superconductors are known: Type I show abrupt loss of superconductivity when an applied magnetic field exceeds a value characteristic of the material. Type II superconductors, which include high-temperature materials, show a gradual loss of superconductivity above a critical field denoted Hc .3 Figure 24.23 shows that there is a degree of periodicity in the elements that exhibit super conductivity. Note in particular that the ferromagnetic metals Fe, Co, and Ni do not dis play superconductivity; nor do the alkali metals and the coinage metals Cu, Ag, and Au. For simple metals, ferromagnetism and superconductivity never coexist, but in some of the oxide superconductors ferromagnetism and superconductivity appear to coexist on different regions of the structure of the same solid. The first HTSC reported was La1.8 Ba0.2CuO4 (Tc 35 K), which is a member of the solid-solution series La2-xBax CuO4 in which Ba replaces a proportion of the La sites in La2CuO4. This material has the K2NiF4 structure type with layers of edge-sharing CuO6 octahedra separated by the La3+ and Ba2+ cations, although the octahedra are axially elongated by a Jahn–Teller distortion (Section 20.1g). A similar compound with Sr replacing Ba in this structure type, as in La1.8 Sr0.2CuO4 (Tc=38 K), is also known. One of the most widely studied HTSC oxide materials, YBa2Cu3O7-x (Tc=93 K; infomally this compound is called ‘123’, from the proportions of metal atoms in the compound, or YBCO, pronounced ‘ib-co’), has a structure similar to perovskite but with missing O atoms. In terms of the structure shown in Fig. 24.11, the stoichiometric YBa2Cu3O- unit cell consists of three simple perovskite cubes stacked vertically with Y and Ba in the A sites

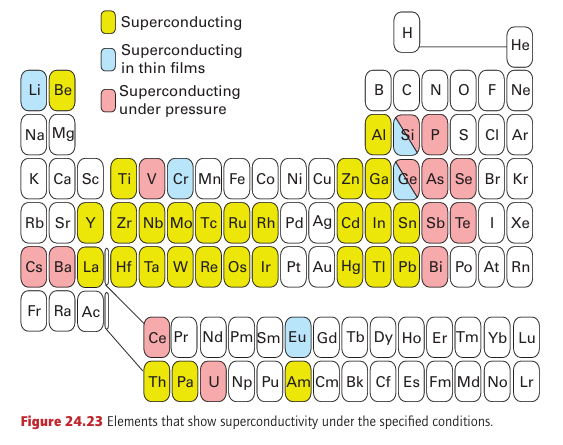

Figure 24.24 Structure of the YBa2Cu3O7 superconductor. (a) The unit cell and (b) oxygen polyhedra around the copper ions showing the layers formed from linked CuO5 square pyramids and chains formed from corner linked CuO4 square planes. of the original perovskite and Cu atoms in the B sites. However, unlike in a true perovskite structure, the B sites are not surrounded by an octahedron of O atoms: the 123 structure has a large number of sites that would normally be occupied by O but are in fact vacant. As a result, some Cu atoms have five O atom neighbours in a square-pyramidal arrange ment and others have only four, as square-planar CuO4 units. Similarly, the Y and Ba in the A sites have less than 12-coordination. The compound YBa2Cu3O7 readily loses oxygen from some sites within the CuO4 square planes, forming YBa2Cu3O7 x (0<x<1), but as x increases above 0.1 the critical temperature drops rapidly from 93 K. A sample of the 123-material made in the laboratory and heated under pure oxygen at 450°C as the final stage of its preparation is typically oxygen deficient with x≈0.1.

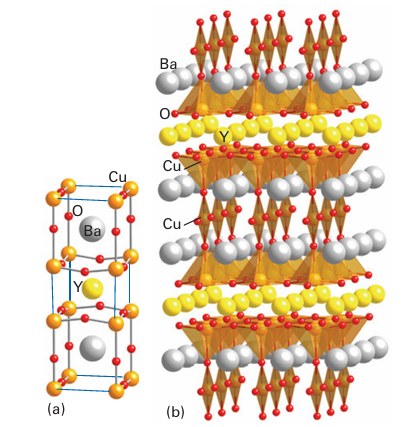

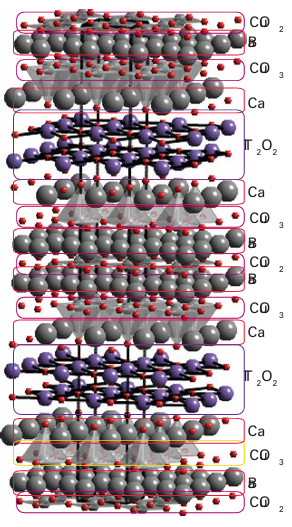

If we assign the usual oxidation numbers Nox (Y)=+3, Nox (Ba)=+2, and Nox(o)=-2, then the average oxidation number of copper turns out to be 2.33, so it is inferred that YBa2 Cu3O7x is a mixed oxidation state material that contains Cu2 and Cu3. Note that in YBa2 Cu3 O7 x the material formally contains some Cu3 until x increases above 0.5. An alternative view is that the number of electrons in YBa2 Cu3O7 x is such that a partially filled band is present: this view is consistent with the high electrical conductivity and metallic behaviour of this oxide at room temperature (Section 3.19). If this band can be considered as being constructed from Cu3d orbitals, then the partial filling is a result of holes in this level (corresponding to Cu3); another possible description is that the band also involves O2p orbitals, suggesting that the material can be considered to contain Cu2 and O-. The square-planar CuO4 units in YBa2Cu3O7-x are arranged in chains and the CuO5 units link together to form infinite sheets. The stoichiometry of an infinite sheet of vertex-sharing CuO4 square planes is CuO2. The addition of one or two additional apical O atoms in the cases where the layers are constructed from, respectively, linked square based pyramids or octahedra maintains the CuO2 sheet. This structural feature is also seen in all other oxocuprate HTSCs. It is thought that it is an important component of the mechanism of superconduction in these materials. Some HTSC and other superconducting materials are listed in Table 24.4. All of them may be considered to have at least part of their structure derived from that of perovskite, as a layer of linked CuOn (n=4,5,6) polyhedra is a section of that structural type. Lying between these cuprate layers (which may include up to six such perovskite-derived CuO2 sheets) can be a variety of other simple structural units, containing s- and p-block metals in combination with oxygen, such as rock-salt and fluorite structures. Thus Tl2Ba2Ca2Cu3O10 can be considered as having three perovskite layers based on Cu, O, and Ca separated by double layers of a rock-salt structure built from Tl and O; the Ba lie between the rock-salt and perovskite layers (Fig. 24.25). The synthesis of high-temperature superconductors has been guided by a variety of qualitative considerations, such as the demonstrated success of the layered structures and of mixed-oxidation-state Cu in combination with heavy p-block elements. Additional considerations are the radii of ions and their preference for certain coordination environ ments. Many of these materials are prepared simply by heating an intimate mixture of the metal oxides to 800–900°C in an open alumina crucible. Others, such as mercury- and thallium-containing complex copper oxides, require reactions involving the volatile and toxic oxides Tl2O and HgO; in such cases the reactions are normally carried out in sealed gold or silver tubes. Thin films are needed if superconductors are to be used in electronic devices. Their preparation is an active area of research and a promising strategy is chemical vapour deposition. The general strategy is to form a thin film by decomposing a thermally un stable compound on a hot solid substrate material (Fig. 24.26). Fluorinated acetylacetonato complexes of the metals (using ligands such as fod, 1) are sometimes used because they are more volatile than simple acetylacetonato complexes. These complexes, such as Cu(acac)2, Y(thd)3 (2), and Ba(fod)2, are swept into the reaction chamber by slightly moist oxygen gas. When conditions are properly controlled, this gaseous mixture reacts on the hot substrate to produce the desired YBa2Cu3O7-x film. The film may be amorphous and require subsequent heating to form a crystalline product. There is, as yet, no settled explanation of high-temperature superconductivity. It is believed that the movement of pairs of electrons, known as ‘Cooper pairs’ and responsible for conventional superconductivity, is also important in the high-temperature materials, but the mechanism for pairing is hotly debated.

Figure 24.25 Tl2 Ba3Ca2Cu3O10 structure formed from three oxygen-deficient perovskite layers produced from linked CuO4 square planes and square-based pyramids separated by Ca on the A type cation position. Double layers of stoichiometry Tl2O2 with rock-salt type arrangements of the Tl and O atoms are interleaved between the multiple perovskite layers.

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء العضوية

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء العضوية

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة