Methods of direct synthesis

المؤلف:

Peter Atkins, Tina Overton, Jonathan Rourke, Mark Weller, and Fraser Armstrong

المؤلف:

Peter Atkins, Tina Overton, Jonathan Rourke, Mark Weller, and Fraser Armstrong

المصدر:

Shriver and Atkins Inorganic Chemistry ,5th E

المصدر:

Shriver and Atkins Inorganic Chemistry ,5th E

الجزء والصفحة:

ص602-603

الجزء والصفحة:

ص602-603

2025-10-08

2025-10-08

286

286

Methods of direct synthesis

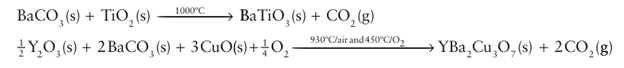

Key point: Many complex solids can be obtained by direct reaction of the components at high temperatures. The most widely used method for the synthesis of bulk inorganic solids involves heating the solid reactants together at a high temperature, typically between 500 and 1500°C, for an extended period. Normally a complex oxide may be obtained by heating a mixture of all the oxides of the various metals present; alternatively, simple compounds that decom pose to give the oxides may be used instead of the oxide itself. Thus, ternary oxides, such as BaTiO3, and quaternary oxides, such as YBa2Cu3O7, are synthesized by heating together the following mixtures for several days:

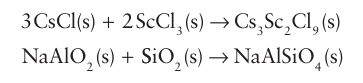

High temperatures are used in these syntheses to accelerate the slow diffusion of ions in solids and to overcome the high Coulombic attractions between the ions. The direct meth od is applicable to many other inorganic material types, such as the syntheses of complex chlorides and dense, anhydrous metal aluminosilicates:

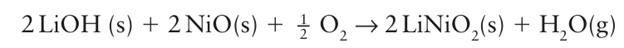

Most simple binary oxides are available commercially as pure, polycrystalline powders with typical particle dimensions of a few micrometres. Alternatively, the decomposition of a simple metal salt precursor, either prior to or during reaction, leads to a finely divided oxide. Such precursors include metal carbonates, hydroxides, oxalates, and nitrates. An additional advantage of precursors is that they are normally stable in air whereas many oxides are hygroscopic and pick up carbon dioxide from the air. Thus, in the synthesis of BaTiO3, barium carbonate, BaCO3, which starts to decompose to BaO above 900ºC, would be ground together with TiO2 in the correct stoichiometric proportions using a pestle and mortar. The mixture is then transferred to a crucible, normally constructed of an inert material such as vitreous silica, recrystallized alumina, or platinum, and placed in a furnace. Even at high temperatures the reaction is slow and typically takes several days. A variety of methods can be used to improve reaction rates, including pelletizing the re action mixture under high pressure to increase the contact between the reactant particles, regrinding the mixture periodically to introduce virgin reactant interfaces, and the use of ‘fluxes’, low-melting solids that aid the ion diffusion processes. The size of the reactant particles is a major factor in controlling the time it takes a reaction to proceed to completion. The larger the particles the lower their total surface area, and therefore the smaller the area at which the reaction can take place. Furthermore, the distances over which diffusion of ions must occur are much greater for larger particles, which are typically several microns in size for a polycrystalline material. In order to increase the rate of reaction and allow solid state reactions to occur at lower temperatures, reactants having small particle sizes, between 10 nm and 1 μm, and large surface areas are often deliberately employed. where an aqueous solution of the metal salt is sprayed on to a hot surface to evaporate the solvent and decompose the salt to a fine-particle oxide. In the synthesis of LiNiO2, by reaction of LiOH and NiO in air

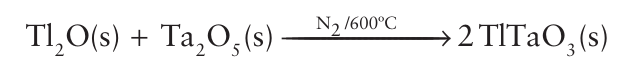

the use of highly reactive nickel oxide particles produced by spray pyrolysis allows the reaction to occur to completion at under 700°C and in only 3 hours, which is at a lower temperature and much faster than would be needed with polycrystalline NiO. The reaction environment may need to be controlled if a particular oxidation state is required or one of the reactants is volatile. Solid-state reactions can be carried out in a controlled atmosphere, using a tube furnace in which a gas can be passed over the reaction mixture while it is being heated. An example of such a reaction is the use of an inert gas to prevent oxidation, as in the preparation of TlTaO3:

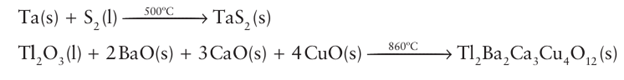

High gas pressures may also be used to control the composition of the reaction product. For example, Fe (III) is normally obtained in oxygen at or near normal pressures but at high pressures Fe (IV) may be formed, as in the production of Sr2 FeO4 from mixtures of SrO and Fe2 O3 under several hundred atmospheres of oxygen. For volatile reactants the reaction mixture is normally sealed in a glass tube, under vacuum, prior to heating. Examples of such reactions are The sulfur and thallium (III) oxide are volatile at the reaction temperatures and would be lost from the reaction mixture in an open vessel, leading to products of the incorrect stoichiometry.

High pressures can also be used to affect the outcome of a solid-state chemical reaction. Specialised apparatus, typically based on large presses, allows reactions between solids to take place at pressures of up to about 100 GPa (1 Mbar) at temperatures close to 1500ºC. Reactions carried out under such conditions promote the formation of dense, higher coordination number structures. An example is the production of MgSiO3, with a perovskite-like structure and six-coordinate Si in an octahedral SiO6 unit, rather than the normal tetrahedral SiO4 unit. Small-scale reactions can be undertaken at very high pressures in ‘diamond anvil cells’ in which the faces of two opposed diamonds are pushed together in a vice-like apparatus to generate pressures of up to 100 GPa.

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء العضوية

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء العضوية

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة