Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Degree modification on pre- and postnominal adjectives

المؤلف:

VIOLETA DEMONTE

المصدر:

Adjectives and Adverbs: Syntax, Semantics, and Discourse

الجزء والصفحة:

p84-C4

2025-04-12

781

Degree modification on pre- and postnominal adjectives

Of course, gradability is not a property which distinguishes between different logical types of adjectives. There are modal adjectives that are gradable: el muy possible acuerdo ‘the very possible agreement’ (but: ∗el muy supuesto asesino ‘the very alleged murderer’) or even event/deictic modifiers which accept degree modification: el muy anterior suceso ‘the very much earlier event.’ However, for the sake of my argument in this work, I will consider gradability as a property of basically two classes of adjectives: pure qualitative ones (los ojos tan limpios ‘such clear eyes,’ el niño menos feliz ‘the least happy boy,’ los más altos cipreses ‘the tallest cypresses,’ la muy seca piel de la niña ‘the girl’s very dry skin’) and deverbal ones (el muy discutido asunto ‘the much debated topic,’ el área completamente protegida ‘the fully protected area’).

Kennedy and McNally (2005) have convincingly argued that gradable adjectives can be partitioned into two semantic classes: relative vs. absolute adjectives. These two classes capture the fact that adjectives, by virtue of their lexical features, have different scalar properties. Absolute adjectives like awake, open, full, or straight have a non-context-dependent standard of comparison:

“they simply require their arguments to possess some minimal [or maximal] degree of the gradable property they introduce”. Relative adjectives like tall or expensive have a context-dependent standard: there is a contextual standard of comparison. In other words, absolute adjectives have a “closed” scale structure while relative adjectives have an “open” scale structure.

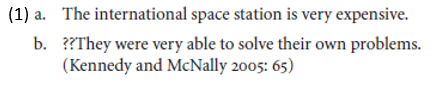

There are many interesting properties which differentiate these two types of adjectives.1 Here, I will concentrate only on the fact that contextual standard of comparison and scale structure affect the grammatical behavior of the degree modifiers which can be applied to gradable adjectives. According to the aforementioned authors, degree modifiers like very, much, and well/completely are sensitive to standard type and scale structure. More strictly, the degree modifier very is restricted to relative adjectives, while absolute adjectives, in normal usage, reject modification by this adverb:

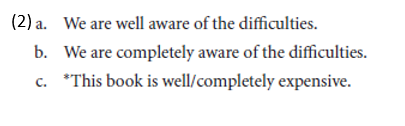

In contrast, degree modifiers like well or proportional modifiers like completely combine with adjectives that have closed scales (2a) and (2b), but not with adjectives that have open scales (8c).

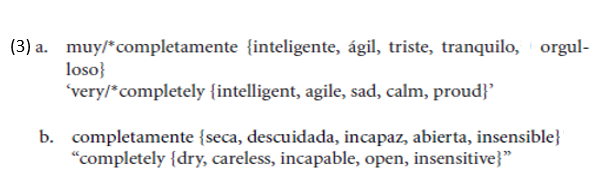

Let us consider now the two series of Spanish adjectives in (3). Those in (3a) are relative adjectives with an open scale and they accept modification by muy ‘very’ but not by the proportional modifier completamente ‘completely.’ Those in (3b) are absolute adjectives with a closed scale such that they can be modified by completamente ‘completely’.2

When relative adjectives with an open scale (3a) are modified by muy, this modifier boosts the (contextual) standard of the property with respect to the objects to which the adjective applies (Kennedy and McNally 2005). When absolute adjectives are modified by completamente this modifier fixes the degree of the property at an endpoint in the structure of the scale that a gradable adjective uses as a basis for ordering objects in its domain.3

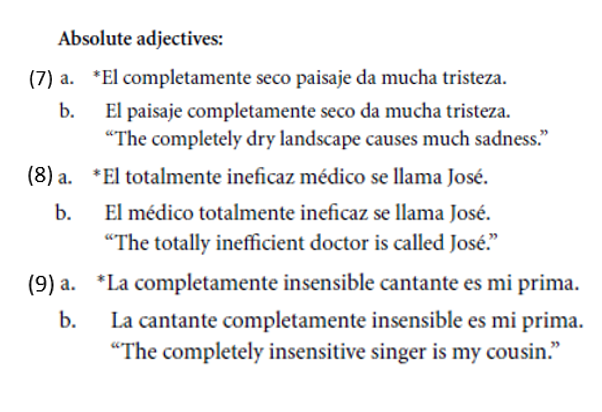

Both types of adjectives can precede or follow N in Spanish DPs. However, the occurrence of both types of adjectives in pre- and postnominal position shows restrictions that depend precisely on the presence of the aforementioned degree modifiers. (In the following judgments, I disregard generic contexts where these distinctions do not hold.)

Observe the facts in (4)–(9). They show that there is a kind of complementary distribution between the two classes: relative adjectives modified by muy are felicitous in prenominal position; however, such a modification sounds awkward – or has to be qualified – when they are postnominal (examples 4, 5, and 6). In contrast, absolute adjectives modified by completamente are almost impossible prenominally, their standard position being the postnominal one (examples 7, 8, and 9) (of course NPs containing prenominal adjectives preceded by completamente are perfectly grammatical if the adverb is removed).

I consider it reasonable to assert that such contrastive behavior constitutes further evidence that pre- and postnominal adjectives have different semantic relations to the N they modify. I am unable to go as far as to establish exactly why fixing of a value on the scale (the function of completamente) helps to fulfill the restrictive function of postnominal adjectives and, at the same time, makes the adjective invalid to be an NR modifier. Perhaps the reason is that absolute adjectives modified by degree adverbs become stage-level predicates and stage-level predicates are not possible prenominally but only postnominally.

In contrast, it is more evident, at least intuitively, in what sense relative adjectives modified by muy help to delineate the central property expressed by the adjective: if the standard of the property is above the normal standard for the N, this property is more likely to be considered central or distinguished.

1 See Kennedy and McNally (2005) for a detailed analysis of relative and absolute adjectives.

2 When modified by very in special contexts, a fact that I do not consider here, they probably change their scalar properties and denote the average degree of the property of an object, thus behaving like relative adjectives.

3 Of course, completamente has other uses which are equivalent to very. Such cases will not be considered here.

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)