تاريخ الرياضيات

تاريخ الرياضيات

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الرياضيات المتقطعة

الجبر

الجبر

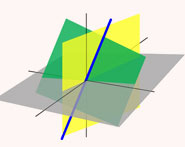

الهندسة

الهندسة

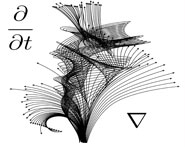

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

التحليل

التحليل

علماء الرياضيات

علماء الرياضيات |

Read More

Date: 29-10-2017

Date: 12-10-2017

Date: 9-11-2017

|

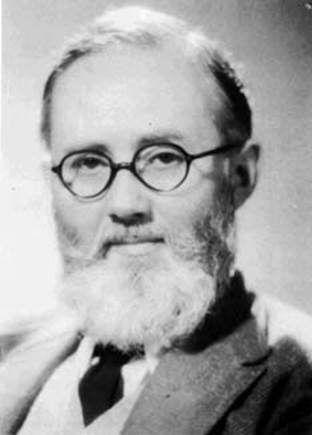

Died: 14 October 1982 in Cambridge, England

Hubert Linfoot's parents were George Edward Linfoot and Laura Clayton. George Linfoot was a violinist and mathematician who was a school teacher of mathematics before becoming Director of Music for the Sheffield Local Education Authority. Hubert was the eldest of his parent's children and their only son. Hubert's sister Laura Margaret Linfoot (1910-1995) became a Fellow and Tutor in Economics in Somerville College, Oxford. Margaret married the government economic adviser Robert Hall. We note the amusing fact that after Robert Hall was knighted, his wife became Lady Margaret Hall. This must have caused confusion in Oxford where one of the colleges is named Lady Margaret Hall.

Linfoot was brought up in Sheffield where he attended King Edward VII school. His record was outstanding and he achieved passes with distinction in Mathematics, Additional Mathematics, Chemistry and German. He took the Oxford scholarship examinations when only 16 years of age and was awarded a mathematics scholarship to Balliol College. However he did not go to Oxford at this young age but waited until he was 18 years old, matriculating in 1923. The lecturer at Oxford who influenced him most was G H Hardy. During 1925-26 he had tutorials from Besicovitch who spent the year in Oxford trying to improve his ability to teach in English. In fact despite still being an undergraduate, Linfoot was already undertaking research and published his first paper The domains of convergence of Kummer's solutions to the Riemann P-equation in 1926.

In 1926 Linfoot graduated B.A. with First Class Honours in mathematics and he was awarded a Goldsmith Senior Scholarship to enable him to undertake research supervised by Hardy. He attended Hardy's seminar along with Stephen Bosanquet and Mary Cartwright who were also Hardy's doctoral students. Three of Linfoot's papers were published in 1928: On the "Law of large numbers" I; On the "Law of large numbers" II; and Generalisation of two theorems of H Bohr. Also in 1928, Linfoot was awarded his doctorate after submitting his thesis Applications of the Theory of Functions of a Complex Variable in which he studied almost periodic functions. His scholarship was extended to allow him to spend the academic year 1928-29 at Göttingen in Germany. There he attended lectures on number theory by Edmund Landau, lectures by Harald Bohr on almost periodic functions (Harald Bohr, although based in Copenhagen, was visiting Göttingen to continue his collaboration with Edmund Landau), lectures on topological groups by van der Waerden, lectures on class field theory by Emil Artin, and lectures by Edmund Landau on Waring's problem and on Schlicht functions. Linfoot had already adopted the practice of taking notes of high quality of all courses he attended, and most of his beautifully written notebooks survive including those of the Göttingen courses he attended. Linfoot already spoke German fluently before his Göttingen visit, and after spending the year in Germany he was often mistaken for being German. In fact the courses Linfoot attended in Göttingen were delivered in German but written up by him in English.

After spending this year in Göttingen, Linfoot spent the next two academic years in Princeton supported by a Jane Eliza Procter Fellowship. His notebooks show the lectures he attended: a course on dimension theory given by Pavel Sergeevich Aleksandrov, a course on quantum mechanics by Howard Robertson, and another course on quantum mechanics by von Neumann. Linfoot returned to Balliol College in 1931 and taught there until he was appointed as an Assistant Lecturer at the University of Bristol in 1932.

Hans Heilbronn was dismissed as an Assistant at Göttingen following the passing of the Nazi racial laws of 1933. He went to the University of Bristol and began lifelong friendship with Linfoot. They published an important joint paper On imaginary quadratic corpora of class-number one (1934). In it they showed that there were at most ten quadratic fields of negative discriminant of class number one (of which nine had been known essentially since Euler). In 1935 Linfoot married Joyce Dancer, the only daughter of James and Ellen Dancer, who was an excellent mathematician; they had a daughter Margaret (born 1945) and a son Sebastian (born 1947). The 1930s were a time of change for Linfoot. Following his year in Germany he became convinced that war was inevitable. This was reinforced by his discussions with Heilbronn and other refugees. Linfoot was determined to serve his country and make a significant contribution to the war effort despite knowing that his poor physical health would mean that he would fail a medical for military service. He therefore moved his research area to optics, believing that this would enable him to contribute to the war effort. His reason for choosing optics was a longstanding interest in astronomy and, when he was a young boy, he had built himself a small telescope. He also spoke of feeling that he had come to doubt his continuing creativity as a pure mathematician (although he published 13 papers in pure mathematics in the 1930s, they were all joint publications, which could indicate that he felt he was helping to solve problems devised by others).

Linfoot began to build optical instruments in the H H Wills laboratory of the Physics Department at Bristol University. He exhibited a microscope of his own construction at the 1939 Exhibition of the Physical Society [2]:-

Linfoot said of this transition that in pure mathematics he needed to learn to think with complete accuracy, whereas in optics he had to learn to think with controlled inaccuracy, and he found this the more difficult of the two.

Although he began his new career in optics with very practical work, he soon began to use his mathematical skills to solve theoretical problems. During World War II, he remained at Bristol but did important work for the Ministry of Aircraft Production on optical systems for air reconnaissance and also for Mott's research group which was trying to provide rapid solutions to problems of a technical nature. An example of a paper he published during World War II is On some optical systems employing aspherical surfaces (1943). P Boeder writes in a review:-

The "see-saw diagram" method of C R Burch (1942) [Burch worked at the H H Wills Laboratory] is applied to obtain general formulas for the Seidel errors, excluding distortion, of optical systems consisting of two mirrors and a nearly plane parallel plate. It is shown that the only flat-fielded anastigmatism with both mirrors spherical is equivalent to the field-flattened Schmidt, while, in general, flat-fielded anastigmat requires asphericity of at least two of the optical surfaces. Nevertheless, special consideration is given to the case where both mirrors are spherical and only the correcting plate is figured. A system is designed suitable for use as an astrographic camera. Although this system is not strictly anastigmatic, it is shown that its field curvature can be satisfactorily controlled. An estimation is given of the performance of the system as compared with that of Schwarzschild's two mirror aplanats.

On 1 June 1948 Linfoot was appointed Assistant Director of the Observatories at Cambridge, and John Couch Adams Astronomer [1]:-

This was an especially propitious moment for him to arrive in Cambridge since the Mathematics Laboratory had just begun its activities and was engaged in the early stages of the construction of Edsac I, one of the first generation of fast computers. The development of these was of crucial importance for optical design, where the sheer weight of the arithmetical calculations constituted a real barrier to progress. Linfoot began almost immediately to write programs which were well received by the laboratory personnel since they ran for a reasonable length of time and so enabled the computer's performance to be properly accessed. He developed at this time a keen interest in computers which came to exercise a strong influence on his thinking.

In [2] an overview of Linfoot's contributions to astronomical optics is given which begins as follows:-

Any summary of his rich contribution to astronomical optics must necessarily be over-simplified, but the main elements may perhaps be characterised as synthesis, error-balancing, assessment and testing. ... One of Linfoot's major contributions to synthesis was to apply his formidable analytic ability to the physical concept of the plate-diagram of Burch; this led, for example, to much of his work on Schmidt-Cassegrain and related systems.

The first of Linfoot's two major books was Recent advances in optics (1955). M Herzberger writes:-

The author has made contributions to geometrical optics, diffraction optics and to the study of coherence in optical systems. His book can be considered as a collection of a series of monographs in special fields of optics in which he is interested. ... The first section deals with the optical image starting from the characteristic function ... The second monograph deals with the Foucault (knife-edge) test, its theory, and its application to the study of aberrations of optical system with small errors. The third monograph deals with the Schmidt correcting plate, to the theory of which the author has made various contributions. The last chapter carries out in detail an idea by C R Burch.

One important aspect of Linfoot's work was his application to optics of new ideas in information theory which had just been published by Claude Shannon. For example he showed how the methods of information theory can be applied to the analysis of the optical images in his article Information theory and optical images (1955). Herzberger also reviewed Optical image evaluation from the standpoint of communication theory (1958):-

This thought-provoking but difficult paper attempts to transfer the concepts developed in communication theory to the evaluation of the optical and photographic image and its information content in the presence of optical "noise".

Applying ideas from information theory, particularly methods of Fourier analysis, to optical images is the main topic of his second book Fourier methods in optical image evaluation (1964). It is worth noting that his papers contain material relating to an unpublished book on almost periodic functions which he had planned to write.

Linfoot's expertise in optics for astronomical instruments led to him being in demand as a consultant for the building of several major telescopes. He was a consultant for the design of a thirty-seven-inch Schmidt-Cassegrain telescope at the University of St Andrews, Scotland, completed in 1962 (initially supervised by Finlay Freundlich), for the 2.5 m Cassegrain Isaac Newton Telescope completed at Herstmonceux, Sussex in 1967, and for the 3.9 m Cassegrain Anglo-Australian Telescope which began operating at Siding Spring, Australia in 1974. The first two of these consultancies are most extensively documented in the papers he left.

As to his character we quote from [2]:-

Linfoot's health was never robust. His need to reserve his effort for what was of greatest importance could give the impression of a more retiring disposition than he in fact possessed, and this contributed to the sense of intellectual loneliness that he undoubtedly felt even in a great university, particularly among astronomers who in the days before radio astronomy and space research tended towards conservatism of outlook. ... He had cultivated tastes not only in music but also in literature and art ... and was a connoisseur of chess and Go.

Articles:

|

|

|

|

التوتر والسرطان.. علماء يحذرون من "صلة خطيرة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مرآة السيارة: مدى دقة عكسها للصورة الصحيحة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

نحو شراكة وطنية متكاملة.. الأمين العام للعتبة الحسينية يبحث مع وكيل وزارة الخارجية آفاق التعاون المؤسسي

|

|

|