النبات

النبات

الحيوان

الحيوان

الأحياء المجهرية

الأحياء المجهرية

علم الأمراض

علم الأمراض

التقانة الإحيائية

التقانة الإحيائية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحيوية المكروبية

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

التقنية الحياتية النانوية

علم الأجنة

علم الأجنة

الأحياء الجزيئي

الأحياء الجزيئي

علم وظائف الأعضاء

علم وظائف الأعضاء

الغدد

الغدد

المضادات الحيوية

المضادات الحيوية|

Read More

Date: 23-11-2016

Date: 30-10-2015

Date: 27-11-2016

|

Origin and Early Evolution of The Angiosperms

Concepts about the nature of early angiosperms have changed as our knowledge of existing and fossil plants has become more complete. In the last century, wind-pollinated members of the subclass Hamamelidae (alders, elms, oaks, plane trees) were considered the most relictual of the living flowering plants and were known as the Amentiferae because their inflorescences are aments (an old term for catkin; Fig.6a). At first glance this classification seems reasonable because these species tend to be woody trees, and most gymnosperms such as conifers are also wind-pollinated trees. Once their wood anatomy was studied, however, it became obvious the Hamamelidae could not be relictual plants because their wood contains vessels, fibers, and abundant parenchyma, features not found in gymnosperms. Furthermore, the flowers of Amentiferae are quite specialized: They often lack sepals and petals and are typically unisexual, occurring as either staminate or carpel- late flowers, not as perfect flowers. It is difficult to imagine how such simple flowers could evolve into the much more complex flowers of other angiosperms.

About 70 years ago, C. E. Bessey developed the hypothesis of the "ranalean" flower, in which a Magnolia-type flower was thought to be relictual (Fig.6b). Such a flower is generalized; that is, it has all parts (sepals, petals, stamens, carpels) and these are arranged spirally. Also, carpels occur in a superior position, above the other parts. This ranalean flower is quite different horn the wind-pollinated flowers of the Amentiferae. It is easier to postulate the evolution of all the various existing flower types from a ranalean, generalized ancestor than from an amentiferous, specialized type of imperfect flower that lacks sepals and petals. For example, an amentiferous flower could evolve easily and quickly from a generalized, Magnolia-type flower by reduction or loss of parts.

This change in the concept of the relictual flower type was dramatic, not only because the differences in structure are so great, but because the ranalean flower is insect-pollinated, whereas gymnosperms are wind-pollinated. However, the magnolias and their relatives, with their ranalean flowers, must be considered relictual, because the wood, with all of its numerous characters, is very similar to the wood of gymnosperms. It is now known that the four orders of flower-visiting insects (bees, butterflies, beetles, flies) had evolved at about the time angiosperms were appearing. They could have pollinated the early flowers, and the co-evolution of flowers and pollinators could have begun.

FIGURE 6: (a) Catkins of alder (Alnus rubra); each of the three main axes bears many flowers, all with stamens but not carpels. Other catkins on the plant would be carpellate and would lack stamens. (C. E. Mills, University of Washington/Biological Photo Service) (b) A flower of Magnolia is considered the typical ranalean flower— similar to that of the early angiosperms. All the parts are rather massive and are not specialized for one particular type of pollinator. Very few flowers have so many carpels, almost always fewer than ten; by contrast, seed cones of conifers and cycads have large numbers of megasporophylls. (Dan Clark from Gat Heilman).

At present, our ideas about the nature of the vegetative body of relictual angiosperms are changing. Considerable doubt exists that plants were heavy, woody trees like either Magnolia or members of the Hamamelidae. Instead, they may have been fast-growing woody shrubs of sunny, somewhat dry, open habitats. They may have diversified, some lines becoming larger and more massive, others smaller and herbaceous. More importantly, we now have greater appreciation for the numerous differences between gymnosperms and angiosperms. The transition of some gymnosperms into angiosperms was gradual. We no longer expect to find one specific ultimate ancestor to the angiosperms or to pinpoint the date of origin. Studies now examine the step-by-step evolution of leaves and the development of a broad lamina with reticulate venation and an elongate petiole. In wood, the origin of vessels, scalariform bordered pits, fibers, and parenchyma is being studied. This same approach is being followed with the evolution of stamens, pollen, carpels, and pollinator relationships.

With new discoveries of fossil gymnosperms and with careful analysis of their microscopic details, we now realize that by the Jurassic Period in the middle of the Mesozoic Era (180 million years ago), many of the gymnosperms had features similar to those we associate with angiosperms. In many evolutionary lines various features were advancing at different rates. Some had leaves with reticulate venation; others had the first stages of scalariform bordered pits in their wood. Several had sporophylls that were beginning to look like carpels, and some of these were being visited by beetles. Almost all of this assemblage of gymnosperms with derived features became extinct; only a few produced lines that are still in existence today, such as the gnetophytes and the angiosperms. Our present task is to determine which of the fossil gymnosperms are part of this evolutionary line. We will almost certainly find a series of gymnosperms that resemble angiosperms more closely in a greater number of features but not a "last gymnosperm" or a "first angiosperm."

If the angiosperms evolved from the mid-Mesozoic assemblage of derived gymno- sperms, how many lines were involved? Most botanists conclude that there was just one, that angiosperms are monophyletic. Features as complex as double fertilization, flowers, and developmental plasticity probably did not evolve more than once.

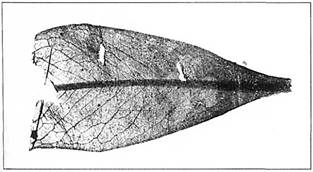

At present, many paleobotanists and taxonomists believe that the transition from gymnosperm to angiosperm occurred during the Jurassic and Tower Cretaceous Periods of the Mesozoic Era. The earliest leaf fossils definitely considered to be those of angiosperms are from the Lower Cretaceous Period, about 130 million years ago. They represent both dicot and monocot leaves, for example Magnoliaephyllum, Ficophyllum (figlike leaves), Vitiphyllum (grapelike leaves), and Plantaginopsis (similar to Plantago) (Fig. 7). These frag- merits are rare in such old rocks, constituting only about 2% of all fossils present. In rocks about 50 million years more recent, from the Upper Cretaceous Period, many more types of angiosperm leaf fossils are present, outnumbering the leaf fossils of gymnosperms and ferns. These Upper Cretaceous leaf fossils originally were assigned to extant genera such as Populus (poplar), Quercus (oak), and Magnolia on the basis of overall shape and size. But careful examinations of fine venation, cuticle, and stomata often show that these fossils are not truly part of modern genera.

FIGURE .7:A leaf of Magnoliaephyllum showing strong similarities to the leaves of living magnolias. However, fine details visible by microscopy show that this is not identical to a true Magnolia leaf. (Courtesy of D. Dilcher, Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida).

The original misidentification of these leaves contributed to the erroneous hypothesis that angiosperms must have originated in the Jurassic Period, become abundant enough to leave a few fossils in the Lower Cretaceous Period, but then suddenly, in the short span of 30 to 50 million years, rapidly diversified into most of the major extant families and even many of the modern genera. After this supposed burst, genera such as Populus, Quercus, and Magnolia would have had to remain relatively unchanged for 80 to 90 million years, up to the present. Such a burst of diversification followed by extreme stability did not seem plausible. With the discovery that the Upper Cretaceous and Tertiary leaf fossils only resemble leaves of modern genera but are not identical to them in subtle features, a much more gradual evolution can be assumed to have occurred. The early angiosperms were well established by the Lower and Mid-Cretaceous Periods, but probably no modern genus was yet in existence, only precursors that greatly resembled modern genera. These would have evolved gradually into true poplars, oaks, magnolias, and so on.

The oldest wood that seems to be from an angiosperm comes from the Aptian Epoch (125 million years ago) of Japan; unequivocal angiosperm wood occurred about 120 million years ago. Flowers and fruits appear for the first time in the Lower Cretaceous Period. which must mean that their forerunners evolved in the Jurassic Period (Fig.8). Often the fossils consist only of abscised carpels or carpels attached to a receptacle. Unfortunately, sepals, petals, and stamens often abscise even while the flower is still on the plant, so they are rarely present with the carpels. The perianth parts and stamens of modern plants also tend to be delicate and to decay quickly rather than fossilize; the same may have been true of the early flowers. Pollen that could have come from either relictual dicots or monocots is found in Lower Cretaceous strata.

FIGURE .8: (a) Part of a flower from the Cretaceous Period; numerous spirally arranged carpels were still attached at the time it died and started to fossilize. The spiral arrangement is similar to that find in flowers of Magnolia and water lily. Below the carpels are spirally arranged scars where slrnctuies abscised; we do not know if they were sepals, petals, or stamens. (b) Part of a fossil fruit, Paraoreomunneapuryearensis, about 60 million years old. It was a winged fruit similar to those produced today by members of Juglandaceae, the family of walnuts and hickories. (a and b, auesy of D. Dilcher, Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida) (c) Fossil of a Hydrangea flower, 44 million years old. This flower is much more modern and derived than that of Figure .8a, having fewer parts. (Courtesy of S. R. Manehester, Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida).

Much attention is now being given to gymnosperms of the Jurassic and Triassic Periods, and the focus is centering on cycadophytes and glossopterids (Fig.9). As more is learned about this group of gymnosperms, we realize how much the various groups had begun to develop angiosperm-like features.

FIGURE .9:A reconstruction of a Glossopteris, a possible relative to the ancestors of flowering plants. The leaves had a prominent midrib and reticulate venation. The leaves were deciduous and the wood had annual rings, indicating that it lived in a temperate climate.

|

|

|

|

مخاطر خفية لمكون شائع في مشروبات الطاقة والمكملات الغذائية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"آبل" تشغّل نظامها الجديد للذكاء الاصطناعي على أجهزتها

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

المجمع العلميّ يُواصل عقد جلسات تعليميّة في فنون الإقراء لطلبة العلوم الدينيّة في النجف الأشرف

|

|

|