Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension

Teaching Methods

Teaching Methods|

Read More

Date: 25-7-2022

Date: 6-6-2022

Date: 2023-07-21

|

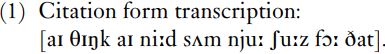

Now we will look at how one piece of speech can be transcribed in a variety of ways, and comment on the transcription.

We will look at a series of transcriptions of the utterance ‘I think I need some shoes for that.’ (The context is two young women chatting about a night out at a graduation ball that they are planning to go to. One of them is discussing the clothes she wants to buy.)

The citation form is the form of the word when spoken slowly and in isolation; this is the form found in dictionaries. Using a Standard English dictionary, we could transcribe this sentence as in (1):

This transcription simply concatenates the citation forms for each word in the sentence. However, in real life, many function words (such as prepositions, auxiliary verbs, conjunctions, pronouns, etc.) in English have other forms called ‘weak’ forms, which occur when the word is unstressed. The word ‘for’ is one such word. Here it is transcribed as , so that it is homophonous with ‘four’. But in this context, a more natural pronunciation would be [fə], like a fast version of the word ‘fur’. (This is true whether you pronounce the

, so that it is homophonous with ‘four’. But in this context, a more natural pronunciation would be [fə], like a fast version of the word ‘fur’. (This is true whether you pronounce the in ‘fur’ and ‘for’ or not!) Likewise, the word ‘I’ is often pronounced in British English as something like [a] when it is not stressed, and ‘some’ as [səm]. So a more realistic transcription of the sentence as it might be pronounced naturally is:

in ‘fur’ and ‘for’ or not!) Likewise, the word ‘I’ is often pronounced in British English as something like [a] when it is not stressed, and ‘some’ as [səm]. So a more realistic transcription of the sentence as it might be pronounced naturally is:

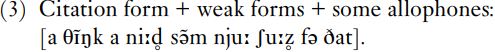

This is a broad transcription; it is also phonemic because all the symbols used represent sounds that are used to distinguish word meanings. It is systematic because it uses a small and limited set of transcription symbols.

We could add some allophonic details to the transcription and make it ‘narrower’. Vowels before nasals in the same syllable – as in ‘think’ – are often nasalized. This means that the velum is lowered at the same time as a vowel is produced, allowing air to escape through both the nose and mouth. Nasalization is marked by placing the diacritic [˜] over the relevant symbol.

Voiced final plosives and fricatives (as in ‘need’, ‘shoes’) are often produced without vocal fold vibration all through the consonant articulation when they occur finally and before voiceless consonants; this is marked by placing the diacritic  below the relevant symbol.

below the relevant symbol.

If we know the sounds and the contexts, these phonetic details are predictable for this variety of English. Not including them in the transcription saves some effort, but the details are still recoverable so long as we know how to predict some of the systematic phonetic variation of this variety of English. This transcription is not only narrower, it is also allophonic: the details we have added are predictable from what we know of English phonetics and phonology.

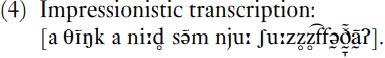

This sentence was spoken by a real person and without prompting, and there is a recording of her doing so. This means that the details are available for further inspection, and therefore can be transcribed. Now we will look at some of the details and illustrate what it means to produce an impressionistic transcription.

The transcriptions so far imply that sounds follow one to another in discrete steps. In reality, things are more subtle. The end of the word ‘shoes’ and the start of ‘for’, [—z f—], requires voicing to be stopped and the location of the friction to switch from the alveolar ridge (for the end of ‘shoe[z]’) to the lips and teeth (for ‘[f ]or’). These things do not happen simultaneously (as the transcription [z f ] implies), so that first we get [alveolarity +friction +voicing], [z], but then the voicing stops, so we have [alveolarity +friction –voicing],  . Since labiodental articulations do not involve the same articulators as alveolar ones, the two articulations can overlap, so we get a short portion of [alveolarity +labiodentality +friction –voicing]. We can represent this as

. Since labiodental articulations do not involve the same articulators as alveolar ones, the two articulations can overlap, so we get a short portion of [alveolarity +labiodentality +friction –voicing]. We can represent this as : the symbol

: the symbol means that two articulations occur simultaneously. The alveolar constriction is then removed, leaving just labiodental friction. So in all, the fricative portion between these two words can be narrowly transcribed as

means that two articulations occur simultaneously. The alveolar constriction is then removed, leaving just labiodental friction. So in all, the fricative portion between these two words can be narrowly transcribed as . This could imply four different ‘sounds’, and at some level, there are: there are four portions that are phonetically different from each other, but really there are only two parameters here: voicing goes from ‘on’ to ‘off ’, and place of articulation changes from ‘alveolar’ to ‘labiodental’.

. This could imply four different ‘sounds’, and at some level, there are: there are four portions that are phonetically different from each other, but really there are only two parameters here: voicing goes from ‘on’ to ‘off ’, and place of articulation changes from ‘alveolar’ to ‘labiodental’.

The end of this utterance is produced with creaky voice. This is where the vocal folds vibrate slowly and randomly. As well as this, the final plosive is not in fact alveolar; like many speakers, this one uses a glottal stop instead. So the last two syllables can be partially transcribed as  . The dental sound in ‘that’ is produced without friction: it is a ‘more open’ articulation (i.e. the tongue is not as close to the teeth as it might be, and not close enough to produce friction): this is transcribed with the diacritic

. The dental sound in ‘that’ is produced without friction: it is a ‘more open’ articulation (i.e. the tongue is not as close to the teeth as it might be, and not close enough to produce friction): this is transcribed with the diacritic (‘more open’); and there is at least a percept of nasality throughout the final syllable. This might be because the velum is lowered (the usual cause of nasality), but sometimes glottal constrictions produce the same percept. We can’t be sure which is the correct account, but the percept is clear enough, and in an impressionistic transcription, it is best not to dismiss any detail out of hand. (For all we know, the percept of nasality might be a feature regularly used by this speaker to mark utterance finality.)

(‘more open’); and there is at least a percept of nasality throughout the final syllable. This might be because the velum is lowered (the usual cause of nasality), but sometimes glottal constrictions produce the same percept. We can’t be sure which is the correct account, but the percept is clear enough, and in an impressionistic transcription, it is best not to dismiss any detail out of hand. (For all we know, the percept of nasality might be a feature regularly used by this speaker to mark utterance finality.)

This probably looks a bit frightening, but it is worth remembering that (a) this is a transcription of one utterance on one occasion by one speaker, and (b) the transcription is based on a set of rather simple observations of what we can hear: it’s more important to understand that relationship than to worry about the details of the transcription. It is important not to fetishize transcriptions, but to see the linguistic patterns that lie beyond them.

These impressionistic transcriptions, as can be seen, use the full range of IPA symbols and diacritics in an attempt to capture details of pronunciation whose linguistic status is not clear. There is no point including details of voice quality in an English dictionary because voice quality does not systematically distinguish words one from another. On the other hand, if it turns out that the speaker whose speech we have transcribed regularly uses creak to mark utterance finality (one possible explanation for what we have found), then transcribing it will have served a useful purpose. Impressionistic transcriptions are therefore often preliminary to further analysis, because they raise a lot of questions.

|

|

|

|

مقاومة الأنسولين.. أعراض خفية ومضاعفات خطيرة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

أمل جديد في علاج ألزهايمر.. اكتشاف إنزيم جديد يساهم في التدهور المعرفي ؟

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

العتبة العباسية المقدسة تقيم ندوة علمية عن روايات كتاب نهج البلاغة

|

|

|