Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 26-4-2022

Date: 2023-10-16

Date: 19-2-2022

|

Emoticons in text-based forms of computer-mediated communication, such as email, SMS texting, Messenger, discussion boards and so on, are generally assumed to constitute iconic indicators of emotion, for example, the use of ☺ to indicate the producer is happy or pleased and the use of

to indicate that he or she is somehow unhappy. While the use of emoticons to index such emotions is a complex topic in itself, Dresner and Herring (2010) have recently argued that emoticons can also be used to indicate the illocutionary force of the text they accompany. In other words, they can be used to help the recipient figure out the speech act(s) being performed by the text message. In the following example from a help chatroom, the guide’s response to a query from a user is accompanied by a smile emoticon.

to indicate that he or she is somehow unhappy. While the use of emoticons to index such emotions is a complex topic in itself, Dresner and Herring (2010) have recently argued that emoticons can also be used to indicate the illocutionary force of the text they accompany. In other words, they can be used to help the recipient figure out the speech act(s) being performed by the text message. In the following example from a help chatroom, the guide’s response to a query from a user is accompanied by a smile emoticon.

JK’s query elicits a response from the guide that appears to be a strong complaint. This could be regarded as unhelpful considering he/she is supposed to be offering advice and information to users in the chatroom. However, the emoticon here functions to index this as “a mild, humorous complaint”, as well as expressing a friendly attitude towards the user. In other words, the illocutionary force of the text message here is modified from a strong to a mild complaint through the deployment of an emoticon

Searle (1979) was not the first to suggest that speech acts could be grouped into more general types. Austin (1975: 150ff.) had, in fact, proposed his own groupings, based on his understandings of a number of performative verbs. The result was not ideal, for a number of reasons, including the fact that some of the categories were less than watertight. Searle (1979) based his taxonomy on a number of pragmatic dimensions. These include the illocutionary point of an act, that is, its purpose (e.g. for a promise it is to create an obligation that the speaker undertakes); the expressed psychological state (e.g. for an apology it is the expression of regret); its degree of strength (e.g. a suggestion is less strong than an insistence); and, importantly, its direction of fit (the relationship between the words and the world). Table 6.2 displays the five speech act categories that constitute Searle’s taxonomy, plus the additional category of rogative, proposed by Leech (1983). Inspired by Peccei (1999: 53), it also displays how those categories vary according to direction of fi t, along with who is responsible for making that relationship happen.

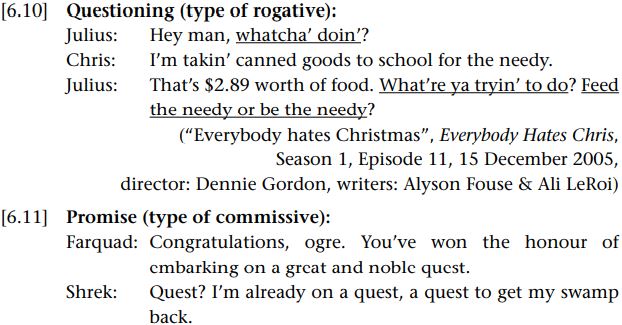

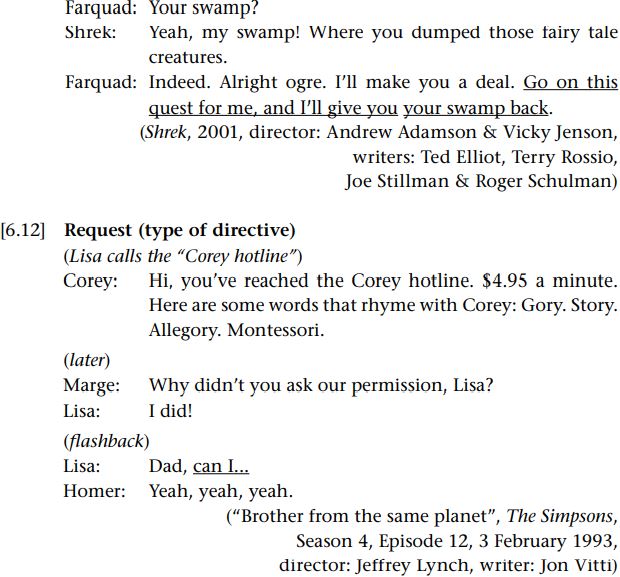

By way of illustration, each of examples [6.7] to [6.12] contain a speech act belonging to each of these types (they are presented in the order of Table 6.2) (key elements in examples are underlined):

|

|

|

|

التوتر والسرطان.. علماء يحذرون من "صلة خطيرة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مرآة السيارة: مدى دقة عكسها للصورة الصحيحة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

اللجنة العلمية لمؤتمر ذاكرة الألم: اعتماد معايير رصينة لتقييم البحوث المشاركة

|

|

|