Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-06-25

Date: 2024-07-06

Date: 2023-08-09

|

The languages of the world fall into two broad classes in terms of stress position. In fixed-stress languages, primary stress always (or virtually always) falls on one particular syllable; thus, in Scots Gaelic, main stress is consistently initial, except in some English loanwords, such as buntata ‘potato’, where stress stays on the syllable it occupies in the source language (here, the second). Similarly, stress in Swahili consistently falls on the penultimate syllable of the word. On the other hand, languages may have free stress, like Russian; here, words which differ semantically may be identical in terms of phonological segments, and differ only in the position of stress, as in Russian ‘muka ‘torment’ versus mu’ka ‘flour’

This division into fixed and free-stress languages is relevant to phonologists because it has a bearing on how children learning the language, and adults using it, are hypothesized to deal with stress. In a fixed-stress language, we can assume that children will learn relatively quickly and easily that stress placement is predictable, and will formulate a rule to that effect; if they encounter exceptions to the rule, they may overgeneralize the regular pattern, and have to unlearn it in just those cases, so that a child acquiring Scots Gaelic may well produce ‘buntata temporarily for English-influenced bun’tata. This is precisely like

the situation with other regular linguistic processes, like the regular morphological plural rule adding -s to nouns, which children typically overgeneralize to give oxes, mouses, tooths at an early stage, before learning the appropriate form of these irregular nouns individually. In free-stress languages, on the other hand, part of language acquisition involves learning that the position of stress is not predictable, but instead has to be memorised as part of the configuration of each individual word, along with the particular combination of vowels and consonants that make it up. There are no stress rules: instead, speakers are assumed to have a mental representation of each word with stress marked on it.

English does not fall fully within either class: it is neither a wholly fixed-stress, nor a wholly free-stress language. This is in large part a result of its peculiar history. English inherited from Germanic a system with fixed stress falling on the first syllable of the stem; but it has subsequently been strongly influenced by Latin, French and other Romance languages, because of the sheer number of words it has borrowed. It has therefore ended up with a mixture of the Germanic and Romance stress systems. On the one hand, there are pairs of words which contrast only by virtue of the position of stress, such as con’vert, pro’duce (verb) vs. ‘convert, ‘produce (noun). This initially makes English look like a free stress language, like Russian, but turns out to reflect the fact that such stress rules as English has vary depending on the lexical class of the word they are applying to. On the other hand, there are some general rules, as in (2), which do allow stress placement to be predicted in many English words.

These stress rules depend crucially on the weight of the syllable: A syllable will be heavy if it has a branching rhyme, composed of either a long vowel or diphthong, with or without a coda, or a short vowel with a coda. A syllable with a short vowel and no coda will be light. As (2a) shows, English nouns typically have stress on the penultimate syllable, so long as that syllable is heavy, which it is in aroma (with a long [o:] vowel or a diphthong [oυ] depending on your accent), and in agenda, where the relevant vowel is short [ε], but followed by a consonant, [n]; this must be in the coda of syllable two rather than the onset of syllable three, since there are no *[nd] initial clusters in English. However, in discipline the penultimate syllable is light [sI]; the following [pl] consonants can both be in the onset of the third syllable, since there are initial clusters of this type in play, plant, plastic and so on. Since [sI] has only a short vowel and no coda consonants, it fails to attract stress by the Noun Rule, and the stress instead falls on the previous, initial syllable.

A similar pattern can be found for verbs, but with stress falling consistently one syllable further to the right. That is, the Verb Rule preferentially stresses final syllables, so long as these are heavy. So, obey (with a final long vowel or diphthong), has final stress, as do usurp (having a final syllable for SSBE, with a long vowel and a coda consonant, and

for SSBE, with a long vowel and a coda consonant, and for SSE, for instance, with a short vowel and two coda consonants), and atone (with a long vowel or diphthong plus a consonant in the coda). However, both tally and hurry have final light syllables, in each case consisting only of a short vowel in the rhyme. It follows that these cannot attract stress, which again falls in these cases one syllable further left.

for SSE, for instance, with a short vowel and two coda consonants), and atone (with a long vowel or diphthong plus a consonant in the coda). However, both tally and hurry have final light syllables, in each case consisting only of a short vowel in the rhyme. It follows that these cannot attract stress, which again falls in these cases one syllable further left.

These stress rules are effective in accounting for stress placement in many English nouns and verbs, and for native speakers’ actions in determining stress placement on borrowed words, which are very frequently altered to conform to the English patterns. However, there are still many exceptions. A noun like spaghetti, for instance, ought by the Noun Rule to have antepenultimate stress, giving ‘spaghetti, since the penultimate syllable [ gε] is light; but in fact stress falls on the penultimate syllable, following the original, Italian pattern – in English, the is of course pronounced as a single [t], not as two [t]s or a long [t]. Although the Noun Rule stresses penultimate or antepenultimate syllables, nouns like machine, police, report, balloon in fact have final stress. There are also cases where the stress could, in principle, appear anywhere: in catamaran, for instance, the stress pattern is actually ‘catama,ran, with primary stress on the first syllable and secondary stress on the final one, again in contradiction of the Noun Rule, which would predict ca’tamaran (as in De’cameron), with antepenultimate stress as the penult is light. There is equally no good reason why we should not find ,cata’maran (as in ,Alde’baran); while another logical possibility, ,catama’ran, has a pattern more commonly found in phrases, such as ,flash in the ‘pan, or ,Desperate ‘Dan. It seems that the Noun Rule and Verb Rule are misnomers; these are not really rules, though they do identify discernible tendencies.

is of course pronounced as a single [t], not as two [t]s or a long [t]. Although the Noun Rule stresses penultimate or antepenultimate syllables, nouns like machine, police, report, balloon in fact have final stress. There are also cases where the stress could, in principle, appear anywhere: in catamaran, for instance, the stress pattern is actually ‘catama,ran, with primary stress on the first syllable and secondary stress on the final one, again in contradiction of the Noun Rule, which would predict ca’tamaran (as in De’cameron), with antepenultimate stress as the penult is light. There is equally no good reason why we should not find ,cata’maran (as in ,Alde’baran); while another logical possibility, ,catama’ran, has a pattern more commonly found in phrases, such as ,flash in the ‘pan, or ,Desperate ‘Dan. It seems that the Noun Rule and Verb Rule are misnomers; these are not really rules, though they do identify discernible tendencies.

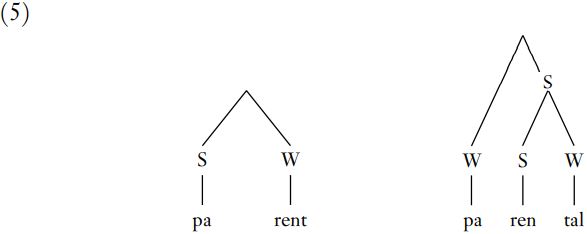

Leaving aside the question of predictability, we can certainly describe the position of stress on particular words accurately and clearly using tree diagrams. In these diagrams, which form part of a theory called Metrical Phonology, each syllable is labelled either S or W: and because stress, as we saw above, is not an absolute but a relative property of syllables, these labels do not mean ‘Strong’ and ‘Weak’, but ‘Stronger than an adjacent W’ and ‘Weaker than an adjacent S’, respectively. Some illustrative trees are shown in (3).

Trees of this sort allow us to compare different words at a glance and tell whether their prominence patterns, and thus the position of stress, are the same or not; from (3), we can see that father and tally share the same stress pattern, though about has the relative prominence of its two syllables reversed. This is particularly important for longer words with more syllables, where prominence patterns are naturally more complex; so, (3) also shows that discipline and personal have the same stress patterns. Note that, even in longer words, metrical trees can only branch in a binary way: that is, each higher S or W node can only branch into two lower-level constituents, never more. This is straightforward enough for disyllabic words like father, about and tally; but in discipline, personal, tree construction involves two steps. Initially, the first two nodes are put together; then the higher-level S node these form is in turn combined with the leftover W syllable, to form another binary unit. This kind of pattern can be repeated in even longer words.

In cases involving both primary and secondary stresses, these trees are particularly helpful: (4) clearly shows the different patterns for entertainment and catamaran. In particular, the trees allow us easily to identify the main stress of each word, which will always be on the syllable dominated by nodes marked S all the way up the tree.

Finally, metrical trees are useful in displaying the stress patterns of related words. In English, as in many other languages, stress interacts with the morphology, so that the addition of particular suffixes causes stress to shift. Most suffixes are stress-neutral, and do not affect stress placement at all: for instance, if we add -ise to ‘atom, the result is ‘atomise; similarly, adding -ly to ‘happy or ‘grumpy produces happily, grumpily, with stress remaining on the first syllable. However, there are two other classes of suffixes which do influence stress placement. The first are stress-attracting suffixes, which themselves take the main stress in a morphologically complex word: for example, adding -ette to ‘kitchen, or -ese to ‘mother, produces ,kitchen’ette, ,mother’ ese. Other suffixes, notably -ic, -ity and adjective-forming -al, do not become stressed themselves, but cause the stress on the stem to which they attach to retract one syllable to the right, so that ‘atom, e’lectric and ‘parent become a’tomic, elec’tricity and pa’rental. The varying stress patterns of related words like parent and parental can very straightforwardly be compared using tree diagrams, as in (5).

There is one final category of word with its own characteristic stress pattern. In English compounds, which are composed morphologically of two independent words but signal a single concept, stress is characteristically on the first element, distinguishing the compounds ‘greenhouse and ‘blackbird from the phrases a ,green ‘house, a ,black ‘bird. Semantically too, the difference is obvious: there can be brown blackbirds (female blackbirds are brown), or blue greenhouses, but The ,green ‘house is blue is semantically ill-formed. In phrases, the adjectives black and green are directly descriptive of the noun, and have to be interpreted that way; on the other hand, the meaning of compounds are not determined compositionally, by simply adding together the meanings of the component parts, so that greenhouse signals a particular concept, with no particular specification of color. Stress is clearly crucial in marking this difference between compounds and phrases; in noting it, however, we are already moving beyond the word, and into the domain of even larger phonological units.

|

|

|

|

التوتر والسرطان.. علماء يحذرون من "صلة خطيرة"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

مرآة السيارة: مدى دقة عكسها للصورة الصحيحة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

نحو شراكة وطنية متكاملة.. الأمين العام للعتبة الحسينية يبحث مع وكيل وزارة الخارجية آفاق التعاون المؤسسي

|

|

|